Information

Ward Tonsfeldt is a retired industrial archeologist, having owned and operated a cultural resource management firm that conducted archeological investigations at mining properties across the Northwest. He has kindly offered the following description of Eric Lamade's mural in the Grants Pass Post Office.

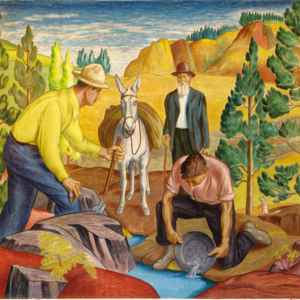

Eric Lamade's excellent WPA mural has five separate scenes arranged chronologically from left to right. The first (left) shows Euro-American immigrants building a log cabin, presumably during the first wave of immigration in the 1840s. The second shows prospecting and pre-industrial mining, perhaps in the 1850s. The next panel shows industrial scale lode mining after about 1875. Panel four shows hydraulic mining after 1900, and the last panel shows irrigated fruit farming (apples, pears) and what looks like hop growing.

The three panels showing gold mining take a little explaining, since mining technology is not familiar to most people these days. Gold mining in the Rogue Valley began at a pre-industrial level in the 1850s, soon after the first Euro-American immigrants arrived in the 1840s. It developed into industrial-scale lode mining during the later decades of the 19th century at selected locations in Jackson and Josephine counties. Then, after the turn of the 20th century, hydraulic and dredge mining prevailed until all gold mining in the US was stopped by War Production Board Order L-208 in October of 1942.

At the time that Eric Lamade painted the mural, gold mining was flourishing in the Rogue Valley. During the national depression small-scale gold mining was a source of income that was not affected by global financial conditions. Individuals could prospect and mine on their own, miners could combine into groups, and small mining businesses could pursue opportunities as they arose. The states with gold resources on public lands — California, Oregon, Alaska, Nevada, South Dakota, etc. — passed legislation to encourage small-scale mining. The federal government supported the states with increases in the price they paid for gold, and in legislation clarifying mining laws on public lands. Here, see Charles W. Miller, The Automobile Gold Rushes and Depression Era Mining

So, in Grants Pass in the late 1930s, Eric Lamade's audience in the post office would have been favorably inclined towards gold mining, perhaps did a little prospecting themselves, and were proud of their region's ability to survive (and even prosper) during the nation-wide hard times.

The prospecting panel (left center) shows a man with a mule or pack horse speaking to two men working a claim. The two prospectors on their claim are shown panning, which is the simplest and cheapest way to extract gold from the ground. Stream bottom alluvial materials are washed in the pan to separate the gold from the mud and black sand. The men could process about one cubic yard of sand and gravel per day by most estimates.

The prospecting panel (left center) shows a man with a mule or pack horse speaking to two men working a claim. The two prospectors on their claim are shown panning, which is the simplest and cheapest way to extract gold from the ground. Stream bottom alluvial materials are washed in the pan to separate the gold from the mud and black sand. The men could process about one cubic yard of sand and gravel per day by most estimates.

The gold in the Rogue Valley is very fine (called oro fino or flour gold) but is elemental gold without chemical contamination. Consequently it does not need smelting, at least in most locations. The findings would have been amalgamated with mercury at the end of the day, the mercury heated in a simple retort, and the resulting "amalgam button" could be sold, or traded for groceries, equipment, or whatever. Lamade understood this type of mining quite well. He could have shown more sophisticated pre-industrial equipment like a cradle or a sluice box, but he didn't really need to.

The next panel (center) shows an industrial-scale lode mine. From the human standpoint, it is important to note that the men working in these large industrial mines are employees — paid by the hour and not very different from other industrial workers. These were the people most affected by the depression. On the other hand, the prospectors and small operators are self-employed and independent. They were the participants in the "automobile gold rushes" of the 1930s. For the technology of gold mining prior to 1942, I believe the best source is Robert Peele's The Mining Engineer's Handbook . The book is over 2500 pages, and contains a remarkable section "Prospecting, Development, and Exploitation of Mineral Resources," by James McClelland — itself over 500 pages.

In the center panel

the man on the left with the geologist's pick is presumably a geologist, and the other two are idealized WPA workers.

the man on the left with the geologist's pick is presumably a geologist, and the other two are idealized WPA workers.

The background of this panel shows a lode mine on the hill. Lode mines are also called hard rock mines and underground mines. The mine complex includes a tunnel into the hill with galleys running into the ore body, shafts to different levels inside the mountain, and a mill to process the ore into gold. The mine itself is in the upper right. It would have had a horizontal tunnel or adit with track for the ore carts to bring the ore out.

In practice, hard rock mining used the drill-and-shoot mining technique, invented in central Europe in the 15th century, and refined in other European areas, especially Spain and Cornwall. (Here see Georgius Agricola De Re Metallica , numerous editions and translations). The miners drilled holes in the rock face (at the end of the tunnel) filled the holes with blasting powder (or other explosives) and shot all the charges simultaneously. The resulting blast dislodged ore and rock. The miners shoveled the ore and rock into ore carts, and the carts ran out to daylight. In the small buildings at the top of the hill, workers would separate the gold-bearing ore from the rock and send the ore down the hill by the ore chute, pictured as a straight line running down the hill. The rock was dumped down the hill as well, simply to dispose of it.

The large building on the sill side is the mill, where the ore was treated to extract the elemental gold. This was done in the Rogue Valley mines by simple mechanical crushing, probably in a stamp mill. The stamp mill was probably steam powered at this time, although the early ones were powered by water. The ore was crushed and the metal extracted by amalgamating with mercury. The waste materials — called tailings — were simply dumped into the large brown piles you see by the mill building.

Note that the mill does not have a smelter, which would be visible by its stacks. Gold in the Rogue Valley was — for the most part — deposited in its elemental form. that comes as a compound requires chemical treatment for the ore with heat and fluxes to change it to elemental form. This process was expensive and unreliable. Most mines with gold that needed smelting sold the concentrated ore to a smelter located many miles away. The concentrate was shipped by rail.

The third mining panel (right center) is the most interesting by far. It is a little problematic since we need the activity shown on the right side of the second mining panel to make sense of it.

The third mining panel (right center) is the most interesting by far. It is a little problematic since we need the activity shown on the right side of the second mining panel to make sense of it.

In hydraulic mining, gold bearing earth is washed from the hill by a hydraulic nozzle called a giant. The water supply for the giant comes from creek diverted at a higher elevation. The water goes though pipes to the giant, gaining pressure as it runs down the hill. The pressure or "hydraulic head" is a gravity drop; there is no pumping involved.

At the back of the panel we see the hillside cut by hydraulic mining — these scars remain and on hills in Josephine County. I might suggest an excellent book here by Richard Francaviglia, Hard Places: Reading the Landscape of America's Historic Mining Districts . The giant is shown at the end of the pipe, and the operator (dressed in blue) stands by the giant, directing its force. The large white cloud is the water from the giant blasting into the hill. The water comes from a higher elevation, and we see it crossing the riffle on an aqueduct, but the perspective isn't quite right, so it looks like the water is running uphill to the giant.

The trough in the middle of the panel, running straight at the viewer, is a sluice box. You can see its wooden sides. The sluice box traps the metallic gold with riffles, which are steel or wooden obstructions across the bottom of the box. The riffles are coated with mercury. The sluice is shown as being quite long. This is correct. I have measured sluices over 400' long on hydraulic mines in California's Klamath District. Whether steel or wooden, the riffles needed to be cleaned out periodically. The giant was turned off (no easy trick) and the riffles were cleaned of their mercury and amalgamated gold. The amalgam was retorted, the mercury was renewed on the riffles, and the sluice was put back in operation.

On the left side of the panel, seen in the previous panel, the man in the pink shirt is standing by a very sophisticated device called an undercurrent. The undercurrent was a large wooden box filled with water that has run through the sluice box, but still carries the finest of the gold particles. The undercurrent is essentially a pool of still water, and the gold settles to the bottom. Excess water flows over the top of the undercurrent, but there is a long narrow opening on the long side of the bottom, which lets a tiny current of water through. This carries the settled gold particles from the bottom of the undercurrent into another recovery system.

Of course, very little gold is mined these days in the Rogue Valley, but it was emphatically positive for Lamade's 1930s audience. We always think that we have a monopoly on environmental sensitivity, but there is good evidence that the residents of the Rogue Valley realized early on the need for caution with some of the new technologies — especially hydraulic mining and dredging. Much of this concern is captured in Oregon Revised Statutes of 1939, chapter 377, "An Act to Provide for Establishing a System of Rotating, Alternating, and Coordinating the Operations of Placer Mines in and along the Waters of the Rogue River and its Tributaries." This is essentially a commentary on Oregon Senate Bill 385 (March 15, 1939) which established standards and enforcement procedures for regulating turbidity in water coming out of placer mines throughout the Valley.