Biography

Winold Reiss's father and grandfather were both artists. The father specialized in paintings of the German landscape and peasants in the Black Forest region. Reiss's early instruction in art came from his father, who sent him to Munich for further study. In Munich Reiss worked under Franz von Stuck at the Royal Academy of Fine arts and Julius Diez at the School of Applied Arts. The contrastings styles of these two teachers would later be fused in Reiss's own work. Von Stuck was an art nouveau artist, designer, sculptor and architect whose students included Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Franz Marc. Diez was a mural painter and designer of commercial Jugendstihl posters, Jugenstihl being an art movement that paralleled the French Art Nouveau. The School of Applied Arts where Diez taught had an unorthodox curriculum combining graphic arts and interior design with landscape and portrait painting.

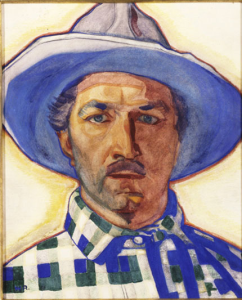

Reiss obtained commercial work in portraiture and advertising. But since childhood he had had a fascination with the American West. After getting married in 1913, Reiss took the leap and emigrated to New York, his wife and newborn son following the next year. His motives probably went beyond his romantic ideas about Native Americans, as the economic situation in the United States may have looked more promising than that in Germany. In any case, Reiss landed on his feet and rapidly found clients among ethnic Germans in New York. He designed hotel and restaurant interiors and was soon doing magazine covers and other commercial art. He quickly gained a reputation for his strong, colorful graphic designs and his very modern commercial interiors.

Reiss lectured at the Art Students League and, with Arthur Wentz, cofounded the Society of Modern Art and its magazine the Modern Art Collector. These efforts helped spread his ideas of modern design and the use of color in the advertising world. His influence on these fields was profound. Upon his arrival in the United States, Reiss felt that New York was "like Germany sixty years ago." Due in no small part to his effort, the interiors of public spaces in New York and other cities were transformed, and commercial art was largely reinvented. Reiss established his own art school in New York in 1916, with students that included Aaron Dougals, Marion Greenwood, Ludwig Bemelmans and Ruth Light Braun. Reiss also set up a summer school in Woodstock, NY.

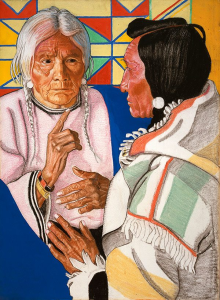

By 1920 Reiss was well enough established to give free rein to some of his earlier ambitions. He travelled to Browning, Montana, where he made drawings of Blackfeet elders and native farmers and ranchers. He spent six weeks in Mexico, depicting heirs of the Aztecs and current-day Mexican revolutionaries. The following year he took his only trip back to Europe, again with an ethnographic focus, this time on peasants in Germany and Sweden.

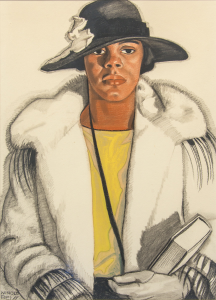

Back in New York, Reiss was busy with portraits of Asian Americans and African Americans. In 1922 Survey Graphic chose him to portray figures of the Harlem Renaissance. This work was continued in 1925, when Alain Locke asked him to illustrate his book "The New Negro: An Interpretation." At Reiss's urging, Aaron Douglas's work was also included in Locke's book. A 1926 Survey Graphic volume focused on Asian Americans, and a 1927 volume dealt with African Americans on the island of St. Helena in South Carolina.

Reiss's trip to Montana led to a long-term association with the Great Northern Railway, whose President purchased Reiss's work in bulk and used it to produce calendars and brochures advertising tourism in Glacier National Park. Great Northern sponsored the Winold Reiss Summer School in Glacier Park in 1931 and 1934-1937. Reiss was an assistant professor of mural painting at New York University, starting in 1933, so the Glacier Park Summer School became a natural adjunct to the education of students in New York.

In 1933 Reiss was chosen to produce a set of Art Deco designs for the Cincinnati Union Terminal. At Reiss's urging, his paintings for this project were implemented as glass mosaics. Reiss knew that the environment of a train station would be very dirty and that canvases would rapidly be degraded. The mosaics, by contrast, could easily be cleaned and would be nearly indestructable. As a result, despite some changes of venue, these works are still available to be seen and enjoyed in Cincinnati. Reiss designed another massive mural for the exterior facade of the Theatre and Concert Building at the 1939 World's Fair.

Reiss purchased a bank building in Carson City, Nevada in 1946, hoping to retire there. But a pair of strokes in 1951 and 1952 left him paralyzed, and he was unable to fulfull this dream. He died the following year.

Critical Analysis

Reiss was a multi-talented individual, at once an artist, a designer, an illustrator, an architect, a printmaker, and a muralist. His work had major impacts in several diverse areas. Early in his career he made highly original contributions to graphic design and furniture design. His art deco graphic design had obvious echoes throughout the 1920s. And his efforts at furniture design included a prototype for an aluminum chair, what became the Emeco 1006 Navy Chair.

Reiss thoroughly reimagined the look of public spaces, saying that restaurant patrons didn't want walls of "brown gravy" to look at and splashing his interiors with bursts of color. In his portraiture he defined the look of figures of the Harlem Renaissance and people of the Blackfeet tribe. More accurately, he brought out the humanity of the people he portrayed and gave them the dignity they deserved. These portraits alone would have made the career of any other artist. But Reiss also designed murals and mosaics to fill the walls of various public spaces.

With so vast an opus, it's hard to compare Reiss with any other artist. It's more that, on his own, outside of Germany, Reiss created a one-man Bauhaus in America. He erased boundaries between fine art and commercial art. And he moved across disciplines such as printmaking, painting and architecture. The Bauhaus also did this, and with a similar aesthetic.

While Reiss had come to New York and found it 60 years behind Germany in its artistic development, there is a sense in which Reiss himself was operating 60 or more years in the future. His interior designs and his portraits still look so fresh that one could easily imagine them to have been newly-created.

Ironically, Reiss's work was largely forgotten after his death. Recent exhibits have renewed attention on his work, but one can easily dismiss his art deco interiors as artifacts of the begone 1920s, forgetting that Reiss had in part invented this approach to interior design. And, worse, Reiss's focus on minority subjects in his portraiture had induced racist gallery owners to ignore these paintings, openly fearing that to exhibit them would invite Black patrons to their shops.

Reiss had an optimism about America and a belief in American citizens of all races that probably transcended the reality of the America in which he lived. Such optimism is a good corrective to the enduring strains of racism that infect the American soul, and it's good to review Reiss's work as an antidote to this disease.

Murals

- Hebron, Kentucky - Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport: Union Station Murals

- Cincinnati, Ohio - Cincinnati Museum Center: Union Station Murals

- Cincinnati, Ohio - Duke Energy Center: Industrial Murals

References

- Victoria L. Valentine, 'Folklorist of the Brush and Palette': Rare Winold Reiss Exhibition Features Distinct, Illuminating Portraits of Harlem Figures, Culture Type May 3 (2018).

- The Art of Winold Reiss, Our Time Press May 5 (2022).

- Ed Voves, The Art of Winold Reiss at the New York Historical Society, Art Eyewitness August 16 (2022).

- The Art of Winold Reiss: An Immigrant Modernist (The New York Historical).

- Biography of Winold Reiss (1886-1953) (Cultural Mobility and Transcultural Confrontations: Winold Reiss as a Paradigm of Transnational Studies).

- Connections: The Blackfeet and Winold Reiss (Indian Arts and Crafts Board).

- Connections: The Blackfeet and Winold Reiss, Indian Arts and Crafts Board 5/26 (2022).

- Jerry Weiss, Modern Design and Portraits of Dignity, The Art Students League June 29 (2022).

- Remembering Russell's West: Portraits of Change (C.M. Russell Museum).

- Where To Be Modern (art reviews from around new york).

- Winold Reiss (Winold Reiss).

- Winold Reiss (Wikipedia).

- Winold Reiss (Hirschl and Adler Galleries).

- Winold Reiss (Lincoln Glenn).

- Winold Reiss (Hockaday Museum of Art).