Biography

Many of the Depression Era artists saw their careers decline as art trends moved away from the American Scene style that had dominated federally-sponsored art programs. Those who did not follow the trend toward abstract expressionism were often forgotten in the world of fine art and perhaps sought alternative careers in the commercial sector.

William Gropper came very close to being one of the forgotten artists from the 1920s and 1930s. His possible decline was helped along by the fact that he was one of only two artists (the other being Rockwell Kent) to be hauled up in front of Joe McCarthy's notorious House Unamerican Activities Committee in 1953. The result of McCarthy's inquisition (and that is a term with the proper historical resonance) was to shut down Gropper's ability to earn a living for nearly a decade. He said that even old friends would shun him after McCarthy's attacks and his refusal to testify before the Committee. Fortunately, he was not jailed for his refusal, and he actually continued to make art, even if he could not sell it immediately. That art included some of his best work, so in that sense McCarthy failed in his goal of destroying a dissident voice.

So where did that voice come from, and how did Gropper acquire such strong resilience? Gropper himself grew up in poverty, and his resilience was born of necessity. His parents were immigrants from Romania and Ukraine. While his father was university-educated and fluent in eight languages, he couldn't find appropriate work in America and ended up - like so many other Jews in New York - working in a garment factory. Gropper's mother earned money from piecework that she did at home - in his memory a veritable slave to the garment industry. It was into this environment that Gropper was born in 1897.

The young Gropper was soon exploring a child's world of art. At age six, he drew block-long sagas on the sidewalks of the Lower East Side. At age 13 (1910) his talent had been recognized to the extent that he could enroll at the newly-formed Ferrer School, a radical enterprise that was explicitly anti-church, anti-state, anti-authoritarian - and dedicated to universal education. Gropper's teachers at the Ferrer School included, amazingly, the brilliant artists George Bellows and Robert Henri.

In 1911 Gropper's favorite aunt was killed in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. This single incident probably defined Gropper's political outlook for a lifetime. The factory's owners had barred the doors to keep workers from taking rest breaks, so most were incinerated in the blaze.

Gropper graduated from public school in 1913 - with a medal in art and a scholarship to the National Academy of Design. But he didn't respect the discipline required at the National Academy and was soon expelled, taking a job in a clothing store. In 1915, however, Gropper showed a portfolio of his work to Frank Parsons, head and founder of the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts. This won him a scholarship, and Gropper continued to work at the store while gaining awards and recognition in his schoolwork.

In 1917 Gropper was hired as a political cartoonist for the New York Tribune. Simultaneously he contributed to left-wing, anti-war publications such of The Masses, which was banned from the U.S. Mail for its opposition to World War I. Gropper joined its successor, The Liberator, and contributed to other publications such as Revolutionary Age and The Rebel Worker. The latter was a publication of the International Workers of the World, and Gropper's involvement with it got him fired from the New York Tribune. During his tenure with the Tribune he was awarded the Collier Prize for illustration.

In 1920 Gropper sailed to Cuba as an oiler on a United Fruit Company freighter. He jumped ship in Cuba and worked supervising a railroad construction crew. His father's terminal illness forced an early return to the United States, where in 1921 he rejoined the staff of The Liberator.

Gropper married Gladys Oaks, another contributor to The Liberator, in 1922. Gropper and Oaks collaborated on Chinese White, a book of drawings and verse, in 1922. But the marriage did not last, and they separated in 1924.

Gropper was a freelance contributor to various mainstream publications in the 1920s. One association that continued for two decades was with the Yiddish publication Morning Freiheit. Gropper started painting privately in 1921. His monotypes were exhibited at the Washington Square Bookshop the same year. He also worked on illustrating books in the years 1921-1923.

In 1924 Gropper took a sketching trip to the American West. He married a bacteriologist, Sophie Frankle, and they built a house at Croton-on-Hudson. Gropper joined the New York World in 1925 and spent a year in the Soviet Union, briefly working for Pravda. He toured the Soviet Union in 1927 in the company of Sinclair Lewis and Theodore Dreiser to mark the tenth anniversary of the Revolution. In 1929 Gropper joined the first John Reed Club, along with artists Hugo Gellert, Jacob Burck, Anton Refregier and Louis Lozowick. It should be noted that regardless of McCarthy's later efforts at defamation, Gropper was never a member of the Communist Party, although he obviously sympathized with the most progressive aspects of Communism.

In 1930 Gropper published Alley-Oop, something that would now be called a graphic novel. He had his first exhibition of paintings the same year. In 1934 he completed two murals for the Schenley Corporation and another mural for the Hotel Taft in 1935. A 1935 Gropper cartoon in Variety produced an international scandal. The work lampooned Emperor Hirohito and led the Japanese government to demand a formal apology from the United States. Needless to say, this did not stifle Gropper's pen.

Gropper held his first one-man show - at the ACA Galleries in New York - in 1936. A Guggenheim Fellowship in 1937 enabled him to travel to the Dust Bowl and visit Hoover Dam and the Grand Coulee Dam. His sketches on this trip formed the basis for his mural for the U.S. Department of Interior Building in 1939. He completed a Post Office mural for Freeport, NY in 1938. And he received the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Purchase Prize in 1939.

Gropper's wartime activities, from 1940-1945, included anti-Nazi cartoons, pamphlets and war posters. He completed a Post Office mural for Detroit in 1941. The War Department Art Advisory Committee selected Gropper to go to Africa in 1943 to make a pictorial record of the front. But, along with Philip Evergood and Anton Refugier, he was denied a passport by the State Department. Following the Warsaw Ghetto uprising Gropper produced "Your Brother's Blood Cries Out." He took first prize for lithography in the 1944 Artists for Victory show and held a one-man show at Associated American Artists in 1944.

In 1945 Gropper covered the United Nations Charter Conference for Freiheit and The New Masses. He painted a map of America with illustrations of regional folklore in 1946. This was one of the exhibits that McCarthy held up ridiculously to accuse Gropper of Communist associations in his 1953 hearing. Gropper was a founder of the Artists Equity Association in 1947 and taught at the American Art School in New York.

In 1948, Gropper attended the World Congress of Intellectuals for Peace, where details of the Holocaust inspired him to pledge to paint one picture a year on the theme of Jewish life. His work was exhibited at the Galeries Benezit in Paris in 1950.

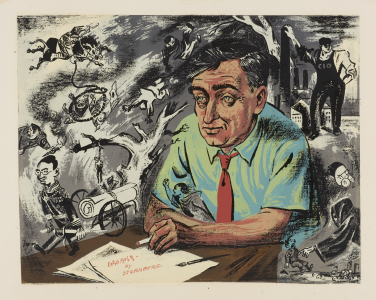

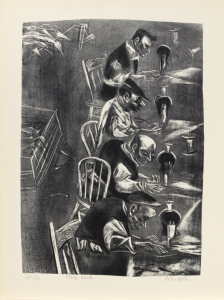

And then came the McCarthy hearings. While Gropper couldn't get paid jobs, he could still make art - and that he did. Inspired by Goya's Los. Caprichos, and funded by private appeals, Gropper produced a powerful set of 50 lithographs in the years 1953-1956. They were exhibited at the Piccadilly Gallery in London in 1956 and at La Galerie del Frente Nacional des Artes in Mexico City in 1957.

As time helped memories of the McCarthy era to fade, Gropper's work began to reappear in the United States. His etchings were shown at the American Artists Association in New York in 1965. And he was invited to design stained glass windows for the Temple Har Zion in River Forest, IL, which were completed in 1967. In 1968 Gropper was elected to the National Institue of Arts and Letters. A traveling retrospective of his work was shown in 1968-1970, and he was named artist in residence at the Museum of Arts and Science in Evansville, IN in 1970. A traveling exhibition of his drawings took place in 1970. An important outgrowth of Gropper's work for the Temple Har Zion was an exploration of his Jewish heritage, expressed in a series of 24 lithographs, The Shtetl, in 1970.

Gropper and Frankle moved to Great Neck, NY in 1971. He died in Manhasset, NY in 1977.

Critical Analysis

In the 1930s Gropper was hailed as the modern-day Daumier. This assessment pretty much still holds true. Gropper's political cartoons remain as fresh as the day they were drawn. Perhaps it's just the fact of having so many ugly people in positions of power that makes the present-day viewer admire Gropper's work so much. But, more likely, it's the way in which Gropper got to the core of human behavior in the traits he chose to satirize.

He was not perfect, of course. Some of his earliest cartoons engaged in racial stereotyping - to the point that he was sometimes called anti-semitic. Part of this arose from his unhappy experience with Jewish education, but more likely it was his inclination to strike out at any figures of authority. In any case, Gropper more than redeemed himself with the Jewish community. The Shtetl is an uninhibited celebration of Jewish life in Eastern Europe, and his Capriccios are a powerful statement on behalf of the downtrodden everywhere.

Murals

- Washington, District of Columbia - Department of The Interior: Construction of the Dam

- Detroit, Michigan - Wayne State University Student Center: Automobile Industry

- Freeport, New York - Post Office: Air Mail

- Freeport, New York - Post Office: Suburban Post in Winter

References

- Joseph Anthony Gahn, The America of William Gropper, Radical Cartoonist (1966).

- Igor Voloshin, An episode from the life of Jewish artist William Gropper, Seagull Magazine September 27 (2018).

- John Murphy, Blacklisted: William Gropper’s Capriccios, Art in Print March-April, Volume 3, Number 6 (2014).

- Samuel D. Gruber, Happy Birthday William Gropper, Samuel Gruber's Jewish Art & Monuments December 3 (2013).

- Richard Kreitner, Let’s Not Forget Socialism in the Resurrection of Socialist Art, The Nation May 12 (2016).

- People Are My Landscape: Social Struggle in the Art of William Gropper (Syracuse University Libraries).

- Kyle Carsten Wyatt, A Popular ’40s Map of American Folklore Was Destroyed by Fears of Communism, Atlas Obscura March 27 (2017).

- William Gropper (Cavalier Galleries).

- William Gropper (Spartacus Educational).

- William Gropper (Wikipedia).

- William Gropper (Helicline Fine Art).

- William Gropper (1897 - 1977) (Central Florida Fine Art LLC).

- William Gropper (1897-1977) (D. Wigmore Fine Art, Inc.).

- William Gropper, 1897-1977 (Trigg Ison fine art).

- William Gropper, American (1897 - 1977) (Ro Gallery).

- John L. Hess, William Gropper, Artist, 79, Dies; Well-Known Left-Wing Cartoonist, The New York Times January 8 (1977).

- William Gropper: Social Realist Art (William Gropper).

- William Gropper: The Capriccios Suite (Wayne State University - University Art Collection).

- Valentina Di Liscia, William Gropper’s Incisive Cartoons in Defense of the New Deal Look Familiar Today, Hyperallergic January 24 (2022).