Biography

Ryah Ludins, her parents and her siblings lived out the saga of immigrant Jews around the turn of the 20th Century. Ryah Ludins's father, David, had trained as an architect but longed to do agricultural work. This was a somewhat Quixotic ambition in a country were he, as a Jew, was forbidden to own land. Unsuccessful in arranging passage to Palestine, David signed up for a Jewish agricultural community forming in New Jersey.

In the course of two years, David had helped build a village in New Jersey, returned to Mariupol, Russia to marry Olga Richman, gone back alone to the United States, and gotten expelled from the New Jersey community for advocating for the farmers' rights. Returning to Mariupol, he and Olga had five children between 1984 and 1903. Laura was born in 1894, Ryah born in 1896, Tima in 1898, George in 1902, and Eugene in 1903. With the rise of pogroms in the region, the couple fled to New York in 1904. While their eldest daughter died in childhood, the other children all had successful professional careers in their adopted country. Tima became a teacher and political activist, George a veterinarian, and Ryah and Eugene were both artists.

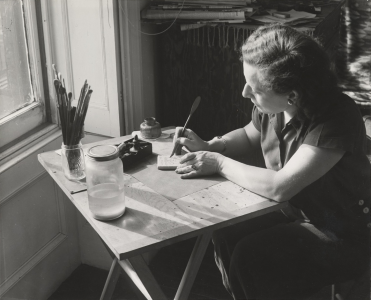

The Ludins family settled in the Bronx, and all of them became citizens in 1911. Ryah studied at the Art Students League with Wiliam Hayter and Kenneth Hayes Miller. She attended Columbia's Teachers College and received a Bachelors of Science in Arts Education.

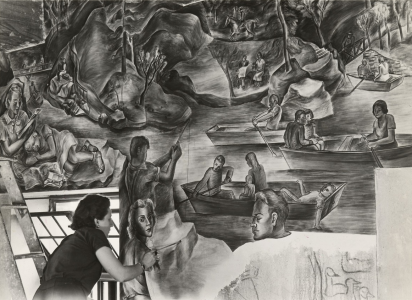

Ryah traveled to Europe with friends in 1925. The frescoes of Giotto and Michelangelo gave her new ambition for a career in art. She returned to Europe in 1926 and stayed to study at the Académie André Lhote in Paris (1926-1928). Back in New York Ryah joined a group to develop a model for creative housing. She was the project's muralist, and her colleagues included an architect, a sculptor and a landscaper. Their work was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art.

Ryah traveled around the country developing ideas for what she called her "phantom murals." She visited industrial sites - the steel mills of Pittsburgh, mines in Ohio and lumber mills in Louisiana - sketching out possible mural designs. Her work began to attract attention - her work was included in Fine Prints of the Year 1931, and she published children's books Adventures in Reading (1928) and The Wonder Rock (1932).

In 1933 Ludins traveled to Mexico City, where she worked with Pablo O'Higgins at the Polytechnic Institute. O'Higgins was a former assistant to Diego Rivera, and Rivera himself encouraged Ludins, saying she had a good mural sense. She was invited to paint a fresco at the Michoacan State Museum in Morelia. She did her research by visiting silver mines in Pachuca and a power plant inn Puebla. Unfortunately her mural "Modern Industry" was never completed after the death of Governor Benigno Serrato.

During her stay in Morelia, she had a short-lived marriage with Juan de la Fuentes, who became Chief of the Department of Labor and Industry. Ludins returned alone to the United States in 1935 and was invited to complete a mural for the recreation room in the Psychiatric Building of Bellevue Hospital on the subject of Central Park. At the time of her return to America, Ryah moved into a suite at the Chelsea Hotel with her sister Tima, where they remained until Ryah's death more than 20 years later.

Ludins completed two Post Office murals: "Cement Industry" for Nazareth, PA (1938) and "Valley of the Seven Hills" for Cortland, NY (1943). A 1939 photograph of her and Balcomb Greene suggests that she worked with Greene on his mural for the Public Health Building at the New York World's Fair. She gave art lessons from her Chelsea Hotel studio, and she taught modern painting and design at Teachers College, Ohio University in Athens, OH and the North Caroliina College for Women in Greensboro, NC. She died in New York from a brain tumor in 1957.

Critical Analysis

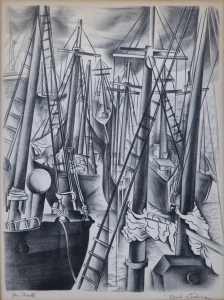

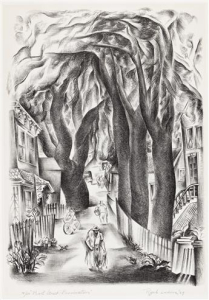

Perhaps influenced by her father, an architect and a builder, Ludins produced drawings and murals that often have a wonderful architectural feel. Whether the subject was a building itself, or a landscape, or even simple scenes of boats in a harbor or trees along a street, Ludins's compositions presented images that were unified in a complete compositional whole. Her tree limbs in "Pearl Street Provincetown" entwine to form a canopy above the street; the masts of her boats in "Masts" are arrayed like houses in a busy and vital urban scene; her industrial murals seem to burst the bounds of the large space allotted to the artwork. Unlike the work of some Depression Era mural artists, Ludins's murals have no blank spaces, no static elements, nothing that seems extraneous to the scene being depicted. This is the "mural sense" that Rivera was able to observe - and that we can still have the pleasure of finding in Ludins's work.

Murals

- Cortland, New York - Post Office: Valley of the Seven Hills

- Nazareth, Pennsylvania - Post Office: Cement Industry

References

- Miss Ryah Ludins, Painter, Teacher, New York Times August 31 (1957).

- Ryah Ludins, Painting Murals in Michoacán, Mexican Life 11, May (1935). pp. 23-23.

- Ryah Ludins (Wikipedia).

- Ryah Ludins (The Women of Atelier 17).

- Ryah Ludins (1896-1957) (ask ART).

- Kim Klausner, Tima Ludins: a life on the left (2003). Tima Ludins was a sister of Ryah Ludins.