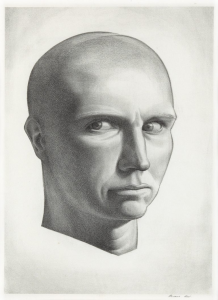

Biography

Rockwell Kent was born in 1882 in Tarrytown, NY to parents George Rockwell Kent and Sara Ann Holgate Kent. George was a successful lawyer, and the family lived in comfort until his death in 1887. Sara's wealthy sister Ellen Josephine Holgate Banker ("Auntie Jo") helped young Rockwell out in more ways than one. She came to live with the family for awhile; she financed Rockwell's private education; herself a ceramicist, she encouraged Rockwell's interest in art; and when he was 13, she took him on an art tour of Europe.

As a student at the Horace Mann School, Kent learned woodworking and mechanical drawing. And he assisted his aunt in painting her ceramics. Awarded a full scholarship, Kent enrolled at Columbia University in 1900 to study architecture. Meanwhile he continued his study of art, composition and design in classes from Arthur Wesley Dow at the Art Students League in the fall of 1900. He also attended William Merrit Chase's Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art in the years 1900-1902. In 1903 he left Columbia to attend Chase's New York School of Art, where he studied with Robert Henri and Kenneth Hayes Miller, and met fellow students George Bellows and Edward Hopper. With a recommendation from Auntie Jo, Kent gained an apprenticeship with painter and naturalist Abbott Handerson Thayer in the summer of 1903.

In 1904 Kent's paintings of Mount Monadnock and New Hampshire were shown at the Society of American Artists, and his "Dublin Pond" was purchased by Smith College. The following year, at Robert Henri's suggestion, he visited Monhegan Island, where he stayed to paint and run an art school for half a dozen years. Auntie Jo arranged to have a one-man show of Kent's Monhegan paintings at the Clausen Galleries in New York in 1907, and this was an important critical success. In 1908 Kent married Kathleen Whiting, who was a niece of Abbott Handerson Thayer. They had five children before their divorce in 1925.

In 1911 Kent was hired by Austin Willard Lord of the New York architectural firm Lord, Hewlett and Tallent to supervise the building of two homes in Winona, MN. He and Kathleen moved to Winona for several years as the project progressed. Having learned carpentry during his stay on Monhegan Island, Kent doubled as foreman of the carpenters on the project. Then, seeing that his carpenters were underpaid relative to those in the town of Winona, he led them out on strike - the first such labor action in the state of Minnesota. Though the strike was settled quickly, Kent continued to twit his employers in one way or another. He also continued painting and even exhibited his work in Winona in 1913.

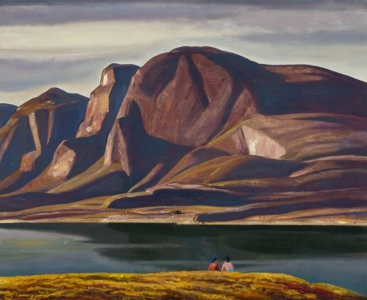

Having been inspired by the rugged landscape of Monhegan Island, Kent sought out even wilder terrains, and in 1914 he took his family to Newfoundland for a year. He had first visited Newfoundland in 1910, thinking of setting up an art school there, but this project had not materialized. His 1914 visit lasted longer, but not without incident. With the onset of World War I, Newfoundlanders worried about German spying operations, and Kent goaded them on with a sign "Private. Chart Room. Wireless Station. Bomb Shop" on his cottage door. This prank went over poorly, and the Kents were expelled from the island.

In 1916 Kent adopted the pseudonym "Hogarth, Jr." to publish satirical drawings in Harper's Weekly and Vanity Fair magazines. He took his 9-year-old son to remote Fox Island in Alaska in 1918-1919, after which he incorporated himself and sold stock to fund the production of his Alaska paintings. Remarkably, a few years later he was able to provide 20% earnings for his shareholders and buy out their stock to liquidate the corporation. He worked on the Alaska paintings in the years 1919-1925 while living in Vermont. He produced a memoir Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska in 1920 that described his Alaska adventures. The paintings and the book were both very well received.

Kent undertook another ambitious trip in 1922-1923, sailing to Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South America and documenting his voyage with drawings, paintings, and a book Voyaging Southward from the Strait of Magellan, which was published in 1924. Following his divorce from Kathleen Whiting, Kent married Frances Lee Higgins in 1926. The couple moved to Woodstock, NY where Kent edited Creative Arts magazine. Kent's marriage to Higgins lasted until 1940, when he divorced her and married Shirly Johnstone. In 1927 Kent purchased land in Au Sable Forks, NY, where he built a dairy farm that he named "Asgaard Farm." This would be his primary residence for the rest of his life.

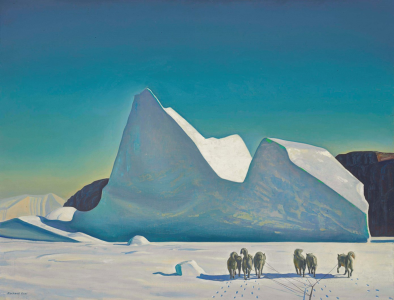

Kent took the first of several trips to Greenland in 1929. He completed murals for the Cape Playhouse and Cinema in Dennis, MA in 1930. Additional trips to Greenland followed in 1931-1932 and 1934-1935. In 1935 Kent returned to Alaska to make studies for a mural for the headquarters of the U.S. Post Office Department in Washington, DC. His "Mail Service in the Arctic" was installed in 1937. This honored the northernmost extent of United States postal service. A trip to Puerto Rico in 1936 prepared Kent to make a mural honoring the southernmost extent of United States mail delivery. That mural, "Mail Service in the Tropics" was also completed in 1937.

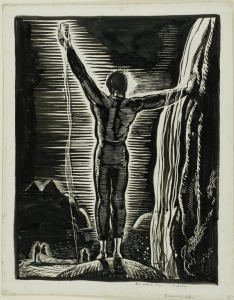

Throughout the 1920s Kent had developed a reputation as a great illustrator. In 1926 R.R. Donnelly invited him to produce an illustrated version of Two Years Before the Mast. But Kent had greater and wiser ambitions, and he suggested Moby Dick as a project for the publisher. A limited edition with Kent's illustrations sold out immediately when it appeared in 1930. Now regarded as one of the greatest works of American literature, the novel was not so well known in 1930, and Kent's brilliantly illustrated edition helped bring Melville's novel into broader public consciousness.

Kent's leftist associations caused him to be hauled up in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1939. Sadly, he continued to be hounded by right-wing politicians for another two decades, and his work was effectively black-listed in the 1950s. John Foster Dulles succeeded in taking away Kent's passport in 1950 - a particularly low blow for such a world traveler as Kent. But in 1958 Kent won a landmark case before the U.S. Supreme Court and had his passport restored. While the McCarthy era blacklist had wrecked Kent's commercial prospects in the United States, he traveled to the Soviet Union after receiving his new passport. Enormous crowds viewed his work during his visit. And in 1960 he donated a large number of paintings and drawings to the people of the Soviet Union. He was given the International Lenin Prize for Peace in 1967, the proceeds of which he donated to the women and children of Vietnam.

Rockwell Kent documented his own life in two autobiographies, "This Is My Own" (1940) and "It's Me, O Lord" (1955). He died in Plattsburgh, NY in 1971.

Critical Analysis

Rockwell Kent was a master of both oil paintings and drawings with a pen or brush and ink. His drawings redefined Americans' concepts of book illustration. While his illustrated Moby Dick is probably his most famous work, traces of Kent's hand are everywhere to be found. For example, the colophons (publishers' emblems) of Random House, Viking and Modern Library were all Kent designs. The Random House colophon originated from the logo that Kent drew for Random House's first book, an illustrated edition of Voltaire's Candide.

Kent's most notable paintings were the product of his explorations of nature. They are largely unpeopled, focusing on the grandeur of nature. These paintings convey a sense of mystery and a recognition of the vast scope of the natural world.

It's interesting to contemplate Kent's firm and unceasing commitment to human rights and his sympathies for left-leaning political groups. While these ideals dominated his personal life – and caused him enormous grief during the persecutions of the McCarthy era – Kent was not really a political artist. He did include a hidden message for Puerto Rican independence in his mural "Mail Service in the Tropics," but this was more of a prank than an overt political statement. In this sense Kent was much less political than, say, Ben Shahn, but he paid a high price for the political views he expressed outside of his art, losing out on nearly three decades of exposure to the art-buying public.

Murals

- Washington, District of Columbia - William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building: Mail Service in the Arctic

- Washington, District of Columbia - William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building: Mail Service in the Tropics

References

- DC - William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building - Mural Tour (Bruce Guthrie Photos).

- Rockwell Kent (Wikipedia).

- Rockwell Kent (National Gallery of Art).

- Rockwell Kent (Annex Galleries).

- Rockwell Kent (ask ART).

- Rockwell Kent (1882-1971) (D. Wigmore Fine Art, Inc.).

- Rockwell Kent Collection (Syracuse University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center).

- Rockwell Kent Collection (Plattsburgh State Art Museum).

- Rockwell Kent in Winona (Rockwell Kent in Winona: A Centennial Celebration). By Taff Roberts.

- Rockwell Kent: A Champion of Peace (Musings on Art). By Cathy Locke.

- Selected Essays on Rockwell Kent (Scott R. Ferris, specialist in the art of Rockwell Kent).