Biography

Mordi Gassner was born into a wealthy family in New York in 1899. He taught himself about art and science in long hours spent at the New York Public Library. He attended the Manual Training High School in Brooklyn, and while he didn't take any special art classes, he did become editor of the school's art magazine. The father was a furrier by trade and had a certain ecological awareness. He had assumed that Mordi would study forestry at Cornell following his graduation from high school. But Mordi's mother had always dreamed that Mordi would be an artist. And, after touring New York art schools with her son, the two settled upon the New York School of Fine and Applied Art (later the Parsons School of Design, but then still run by its founder, Frank Alvah Parsons).

Gassner was assigned to the advertising track at the School of Fine and Applied Art, but he took classes in all branches of art, including interior design, interior architecture, illustration and fine art. Gassner graduated in 1919, the same year his father died in an automobile accident. He worked briefly on naval camouflage, developing ideas that he likened to what came to be known as Op Art.

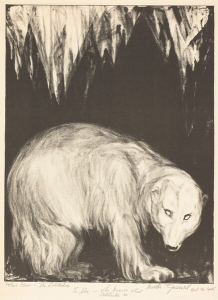

Following World War I, Gassner opened a studio in midtown Manhattan with a fellow student, and the two earned some money producing advertising signs, in a style that Gassner described as proto-art-nouveau. Several things were going on in Gassner's life at this time. Through his father, he had met a furrier who wanted Gassner to produce wild animal paintings with which to decorate his salon. But Gassner had strained his eyes badly in the course of his studies, and his ophthalmologist recommended that he get outdoors and avoid any close work for awhile. Gassner's solution was to combine these two ideas and take a long walk - a very long walk - where he could observe animals for inclusion in future paintings. He started walking in El Paso, went up to the Grand Canyon and then headed south to Phoenix (a trek of some 800 miles), where he stayed with a relative and turned some of his sketches into paintings.

From Phoenix, Gassner continued on to Los Angeles. It's unclear if he continued to travel on foot, but once in Los Angeles, he somehow met Douglas Fairbanks, who promptly offered him a job as art director on his next film. Through Fairbanks he also met Cecil DeMille, with whom he developed a long-term working relationship.

Gassner didn't care for the working environment of the film industry and, when offered a job back in New York in 1924, he decided to leave the West Coast. The job, however, was not a normal one. Back in New York, he found himself teaching art to a group of delinquent boys under a program set up by the Big Brother movement. A psychiatrist with the Big Brothers felt that the boys' antisocial behavior stemmed from a desire for attention and suggested that art might be a healthy way to attract attention. And while Gassner had never taught previously, this little program was a major success. It gotten written up in the New York Times, and all 14 of the boys that he taught ended up with careers in art. Gassner attributed part of his success to the fact that he taught, not only the mechanics of art, but how to prepare materials that could have some permanency. And his students were thus prepared to teach art and art preservation.

Gassner's first exhibits were in 1925. In 1926 he married Augusta Klausner, a modern dancer. Gassner's studies at the Public Library and his experiences with his young students had given him a vision of the potential of the 20th century and New York's role in that century. He thought that the 20th century could fulfill the dreams of the Italian Renaissance and imagined a work that would dramatize this through a marriage of art and science.

Gassner credited Henry W. Kent of the Metropolitan Museum of Art with pushing him to develop this ambitious theme. With this in mind he applied for and won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1928 with the expectation of traveling to Florence. But commitments for a mural in Brooklyn and a contract with Squibb Pharmaceuticals meant that he could not accept the Fellowship that year. He applied again the following year and won once more, allowing him and his wife to spend much of 1928-1930 in Italy. Their daughter Judith was born during this sojourn.

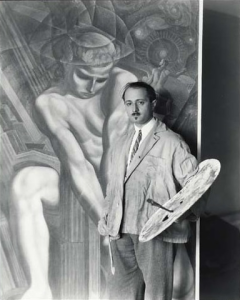

Back in New York, Gassner had a number of commissions for murals and portraits. He completed murals for a Long Island Courthouse and for Temple House and the Granada Hotel in Brooklyn. In 1932 Gassner exhibited the fruits of his Italian project at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Entitled the "Mural Monument to Modern Culture" and planned as a fresco, his project had advanced to the stage of cartoons for the various panels of the fresco, which he had originally hoped to be able to install in a new building in New York. Gassner's cartoons were later shown at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington and the Academy of Art in Richmond, VA. They were lost for many years, but in 2001 five panels were recovered, restored and hung at the Polytechnic University in Brooklyn. Given the onset of the Depression, Gassner's hoped-for fresco was never completed, but he carried over the inspiration for this work into his later efforts in film and writing.

Henry W. Kent made an effort to have Gassner's magnum opus placed at the top of the RCA Building, but an anti-semitic partner in the construction firm for Rockefeller Center refused even to look at any of Gassner's work. The same firm was famously involved in the destruction of Diego Rivera's mural for the same site. This event was a stimulus for protest in the artistic community, and Gassner became involved with the Artists' Union in 1934. He noted that, in the middle of a Depression, one could learn about unionism very quickly.

The wild animal lithographs from Gassner's Western trek were completed in 1936, And Gassner did Post Office murals for Oxford, NY in 1941 and Lynden, WA in 1942.

The Artists' Union was one of the forces behind the formation of the Public Works of Art Project, and Gassner could have continued in that sort of work. He was named supervisor of the National Youth Administration for the metropolitan region, but he was called back to Hollywood, with the opportunity of working as art designer with Orson Welles. That project fell through for a lack of financing and the hesitation of RKO management to undertake a project that seemed critical of the Nazis.

With the onset of World War II, Gassner tried to resume his earlier work in camouflage, but infrared photography had made his previous approach unworkable. He ended up designing and producing visual aids for the Army Signal Corps. Continuing his wartime experience, Gassner turned briefly to industrial design, working on a range of products that included radios and microfilm readers. But he realized that his forte was in art and abandoned that line of work.

After the War, Gassner began a long career as a stage and costume designer, which took him from Broadway to television and to the opera. This occupied him from the late 1940s through his retirement in 1971. In the 1950s and 1960s Gassner also taught art history, painting and scenic design at the New School of Social Research and the Art Students League, influencing a whole generation of artists.

Following his retirement, Gassner and his second wife, Marion Levine, moved to Drakes Branch, VA, cementing ties he had first forged in his 1932 Richmond exhibit. They lived in an old Baptist church in Drakes Branch until Gassner's death in 1995.

Critical Analysis

Mordi Gassner was a Renaissance Man - in several senses of the phrase. He was largely self-educated, and this education spanned both the arts and the sciences. This broad range of knowledge colored his professional accomplishments and the focus of his preferred art.

If one goes through Gassner's career, one can see again and again how he was able to move outside the boundaries of a strict job description and add new and unexpected elements to his creative work. An early example is his work in World War I, just months out of the New York School of Fine and Applied Art. Gassner had the idea of hiding naval targets from enemy gunners by creating visual confusion. So he painted ships with dizzying geometric patterns, making it hard for a gunner to focus on vital elements of the ship while creating confusion about where these elements were actually located. In another era, the style of painting that he used would be known as Op Art.

Gassner's work with delinquent boys is another example of his going far beyond basic requirements of a job. He both inspired his charges and created a curriculum that went beyond what was strictly necessary but which provided his students with a strong basis for future careers.

Gassner's murals for the Granada Hotel led to another innovation. The walls of the dining room where his murals were to go backed up against a kitchen in the next room. Gassner recognized that oil paint would not hold up against the temperature variations in this environment, so he determined to use egg tempera, which he had discovered from an article in the Encyclopedia Britannica and developed through rare books ordered from Europe. Gassner claimed that his Granada Hotel mural marked the reintroduction of egg tempera painting into the United States.

When Gassner was involved with the Artists' Union, he felt that the Union should be coming up with viable projects for unemployed artists, not just advocating for some sort of employment. One of his ideas was to propose a series of murals for the Sixth Avenue subway, then under construction to reach the New York World's Fair. He not only worked out color schemes for the various stations that would assure subway riders that they knew where they were; he even worked with a paint chemist to develop new coatings that would assure the longevity of his proposed outdoor murals. These techniques were later adopted by Rivera, Siquieros and other Mexican muralists.

With the onset of World War II, Gassner tried to resume his earlier work in camouflage, but infrared photography had made his previous approach unworkable. So he applied himself to preparing visual aids such as manuals and wall charts for the armed forces. Here, too, he supplied small but meaningful innovations, such as creating plastic flip-charts so that one could see the different layers that went into the making of a complex piece of machinery.

Gassner's greatest artistic effort was to have been his Mural Monument to Modern Culture. He explained that he viewed the Italian Renaissance as a "vestibule" for the 20th century - the era during which humanity might achieve the promise of the Renaissance for an assertion of the dignity of man. This promise was cut short by the Depression, the rise of fascism and, ultimately, the development of nuclear weapons.

Interestingly, when Gassner went back to Hollywood at the end of the 1930s, one of the projects under way was an Orson Welles film based on Rip Van Winkle. Welles's Rip Van Winkle would have fallen asleep in 1919, dreaming of Woodrow Wilson's promise of a world without war. He would have awakened to the cries of Hitler and Mussolini in the 1930s - an apt metaphor for the death of Gassner's own idealism.

What survives of this idealism is the artistic work that Gassner produced. His cartoons for the Mural Monument to Modern Culture still exist, even if the proposed fresco was never completed. And examples of his other artwork can still be seen. Gassner's Post Office murals are still on view, although they are not his most inspired creations. Curiously, the compositions for Oxford, NY and Lynden, WA are very similar. Each is developed in three sections, the central one being the tallest. The left side of each mural is almost identical in both cases, involving Native Americans in a canoe. Gassner was actually given the subject for the Lynden mural, so the similarities may be only coincidental.

Murals

- Oxford, New York - Post Office: Family Reunion on Clark Island: Spring 1791

- Lynden, Washington - Post Office: Three Ages of Phoebe Goodell Judson

References

- Mordi Gassner (Art of the Print).

- Bibb Edwards, Mordi Gassner, Just an Analog Guy in a Digital World March 8 (2008).

- Mordi Gassner (National Gallery of Art).

- Mordi Gassner Biography (The Annex Galleries).

- Mordi Gassner, 95, Designer and Painter, New York Times January 14 (1995).

- Mordi Gassner, Science-Subject Mural Panels: Astronomy, Biology, Chemistry, Geology, Physics (NYU Arts, Culture, and Entertainment).

- A Mothballed Mural, The New Yorker October 14 (2001).