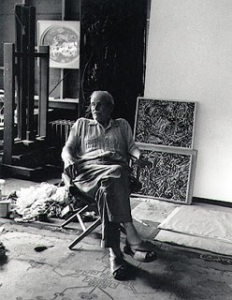

Biography

Lloyd Raymond "Bill" Ney was a person who always followed his own star. We know something about his life and personality from a brief biography written by his granddaughter, Odile Laugier, that is regularly quoted by dealers in his art (often without attribution), from the detailed and insightful thesis of Louise Feder, and from materials at the Michener Art Museum. Unlike some artists whose parents and grandparents had also been in the arts, Ney developed his interest with no formal teachers. But his parents recognized his talent, and he left high school in 1913 to study at the Industrial School of Art in Philadelphia.

Ney transferred to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art of Philadelphia (PAFA) a year later, graduating in 1918. He was, however, not fond of his experience in art school. The school had Ney drawing from plaster casts of famous sculptures, often draped with cloth and hair, challenging the students to capture the exact tone of every fold and curl. While he may not have liked this approach, he did well and won the Cresson Travelling Scholarship in 1920, which provided him with an introduction to art in Europe over the next four years.

In Paris Ney happily rediscovered the intuitive love for painting that he had carried through his childhood. His natural bent was toward nonrepresentational art and color, and he found these elements in European painters of that era. Returning to America, he moved to New Hope, Pennsylvania, where there was a thriving school of painters, focused, however, upon an impressionist style out of keeping with Ney's interests. Nonetheless he persevered, taking some teaching jobs and developing his own style and philosophy of painting.

Things came to a head in New Hope in 1930, when Ney's submission for a local exhibition was turned down. He responded by organizing a rival exhibition with other abstract painters of New Hope, upstaging the original event. This exhibition raised the profile of participating New Hope modernists and led to many opportunities for Ney himself. Positive reviews of Ney's solo show at the Guild Gallery in New York gave him the confidence to submit a design for the St. Louis Post Office as part of a Section of Fine Arts competition. While Ney's proposal was rejected, the jury suggested that he be offered a commission at a smaller post office, which is how he came to do his New London mural.

Ney's cartoon for New London was simple and non-controversial, but in moving to a final design he filled in the cartoon with a collage of images from the town's history. Ney had wisely spent time in New London and talked to many of the townspeople to get a feel for the history of the place and the inclinations of its inhabitants. As a result, while the Section initially rejected Ney's design, public pressure from, among other, the Rotary Club of New London, convinced Section officials to let Ney go through with his proposal. And, contrary to the officials' expectations, Ney's mural was enthusiastically received by the town and remains a point of pride in the community.

Ney may have hoped that his New London project might mark a breakthrough for public support of abstract art. But the advent of World War II meant that the art programs of the Depression years were all winding down, and New London failed to set such a precedent. After the war, it turned out that the very officials who had squabbled with Ney over the New London project came to see him as a major artist and helped him launch a long-term relationship with the Guggenheim Musuem, whose permanent collection includes three of Ney's pieces.

In his post-war work Ney moved completely to nonrepresentational art, retaining his love of intense color and whimsical forms. His work remains popular with art dealers to this day.

Critical Analysis

Over his career Ney developed a philosophy of art, with parallels to the thoughts of Wassily Kandinsky. Ney postulated three groups of art in his manuscript "Art Appreciation for the People! How to Look at Paintings! What Constitutes a Work of Art!" The first group he labeled "Imitative," which includes anything portraying the real. He dismisses this vast category with a broad brush, suggesting that every cycle of imitation just produces something more mediocre than what preceded it. The second group is "Abstract," into which his own New London mural falls, since it includes a large number of images referring to the history of New London, even if they are rendered in fantastical colors with disembodied figures. Ney's third group is "Nonobjective," which he regarded as the pinnacle of artistic achievement.

There is no question that progression from one of Ney's groups to another involves a major shift in one's outlook. Consider, for example, a little road trip in central Ohio. One could stop at the Post Offices in Crestline and Willard and see paintings by Gifford Reynolds Beal and Mitchell Jamieson, respectively. Both show railroad scenes and capture something of the industrial history of the region. But these images hardly prepare one for the fabulous burst of color that greets visitors to the New London Post Office. Here, suddenly, is abstract art! The transition from Abstract to Nonobjective is another great leap, which the Section of Fine Arts never made, but which subsequent programs of the General Services Agency certainly did, as nonobjective art became a dominant style in the art world.

Murals

- New London, Ohio - Post Office: New London Facets

References

- Lloyd (Bill) Ney (Bucks County Artists Database).

- Lloyd Ney (askART).

- Lloyd Ney (Jim's of Lambertville).

- Louise Feder, Lloyd Ney's "New London Facets:" Abstraction and Rebellion in the Section of Fine Arts (2013).

- Gwen Schrift, Lloyd Ney's work embraces a lively era in New Hope history, Phillyburbs June 26 (2016).

- Lloyd Raymond Ney (Margaret Lefranc).

- Tag Archives: Ney (Lloyd). Oral histories with Bucks County artists who mention Lloyd Ney.