Biography

James Henry Daugherty was born in Asheville, NC but spent his early childhood in a bucolic setting along the Wabash River near Lafayette, IN. From his uncles and grandfather he acquired a romantic vision of America. His father obtained a job as statistician for the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the 1890s, at which point the family moved to Washington, DC.

In 1903 James enrolled in an evening drawing class at the Corcoran Gallery's Free School of Art. In the summer of 1903 he also participated in the Darby School of Painting, one of the many summer art camps operating in that era. The Darby School was run by Professors Thomas Anshutz and Hugh H. Breckenridge from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). Anshutz had studied under Thomas Eakins at PAFA and had succeeded Eakins as anatomy instructor in 1886.

The Darby School encouraged individuality. Students would make sketches outdoors and complete their compositions in the studio. Daugherty was praised for his work, but his professors suggested that he might consider illustration if he wanted to make money from his artwork.

In his senior year at Central High School, Daugherty published his first illustration - for "Treasure Island." More polished work of his stemmed from his sketches of Rock Creek Park - a working example of the Darby School method.

Daugherty entered PAFA for training in illustration in 1904. His instructor was Henry McCarter, who counted Arthur B. Carles, Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler - all future modernists - among his students. McCarter emphasized draftsmanship first and foremost, feeling that interpretive elements could follow. Daugherty also studied briefly with William Merrit Chase, who commuted from New York to teach in Washington. While Daugherty later minimized the value of his formal instruction, he did form significant friendships with Carles, Sheeler and Ralph Boyer, among others.

In 1905 James's father became London agent for the Department of Agriculture, and James joined his parents in England. There he studied at the London School of Art, working under Sir Frank Brangwyn. Brangwyn was an influential muralist of the era, and his strong work ethic impressed Daugherty.

Before returning to America, Daugherty read Walt Whitman's "Leaves of Grass," an experience that reinforced his romantic leanings from childhood and echoed throughout Daugherty's paintings of the 1920s and 1930s. Between 1908 and 1911 Daugherty hesitated between painting and illustration. He met Arthur Covey, who had been Brangwyn's assistant from 1903-1908 and was now living in Leonia, NJ. Daugherty joined him there in 1909. The location was convenient to publishers across the river in New York City, and Daugherty received a number of assignments to create illustrations for these publishers.

The years 1911-1915 marked a period of change. His income from illustrations now gave him enough money to buy materials for painting. He moved to Brooklyn Heights in 1911 and immersed himself in the tide of modernism that was then sweeping the art world. He married the writer Sonia Medvedeva in 1912 and attended the Armory Show of 1913, which some of his friends had helped to organize. At that time he was interested in the Futurist style. His interests broadened when he met Arthur B. Frost, Jr., who had studied with Matisse and with Robert and Sonia Delauney. Frost taught Daugherty the Delauneys' theory of Orphism and the theory of Synchromism. The color esthetics of these theories would influence much of Daugherty's later work.

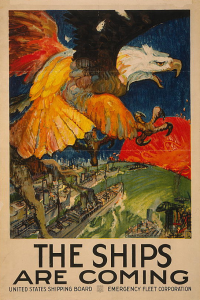

Daugherty continued to do art through World War I. In 1917 he created propaganda posters and volunteered to work on camouflage for the U.S. Navy. Interestingly, he viewed this work as an opportunity for artistic experimentation, treating the side of a ship as a huge canvas on which to try out various color combinations. He called his 1920 mural commission for the State Theater in Cleveland "post-war art," meaning that he viewed the panels of the mural like the sides of the warships he had painted. The idea was to emphasize color, mass and contrast, with details of the artwork being secondary. This approach worked, in that the Cleveland mural was quite well received.

In 1919 Daugherty returned to New York and exhibited with the Society of Independent Artists. He joined the Société Anonyme, which Katherine Dreier and Marcel Duchamp had formed to promote avant-garde art, and participated in their shows over the next few years. In the mid-1920s Daugherty also illustrated dozens of books and became the staff illustrator for The New Yorker magazine.

In 1923 Daugherty moved to Weston, CT, which had become a magnet for artists and writers. He joined the Guild of the Seven Arts in Darien and the Silvermine Guild of Artists in New Canaan and exhibited his mural designs at Guild showings in 1930 and 1931. Participation in a group show at the Montross Gallery in New York in 1933 helped solidify his reputation as a mural artist. With the start of federal programs in the arts, Daugherty was well-placed to receive government commissions.

In 1934 he won contracts for murals in schools in Darien, CT and Stamford, CT. Other murals followed in Greenwich, CT, Bridgeport, CT and Stamford, CT in 1935. Meanwhile, his reputation as an illustrator continued to grow. He received the Caldecott Medal for his illustrations for the children's book "Andy and the Lion" in 1938 and the John Newberry Medal for "Daniel Boone" in 1940. His Virden, IL Post Office mural was his last effort at mural painting, after which he focused primarily on illustration.

In 1953 Daugherty resumed painting and drawing, but in a nonobjective abstract style, unlike the blend of realism and modernism that had been so successful in his earlier work. He received a second Caldecott Medal in 1957. He lived in Weston until his death in 1974.

Critical Analysis

Daugherty's career is itself a lessons in the possibilities and limitations of the federal art programs of the 1930s. On the one hand, Daugherty did receive a number of mural commissions from these programs, and a portion of his work survives in this form. If, on the other hand, you look at his unsuccessful proposals, you have to think that there were a lot of sadly missed opportunities. He had proposals for the New York Customs House (awarded to Reginald Marsh) for Rockefeller Center, and for the St. Louis Post Office. And one of his murals that was produced was later taken down - with the complaint that it was too colorful!

Also, while fellow artists Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, Reginald Marsh and John Steuart Curry were well-known for their murals in the 1930s, Daugherty did not achieve this level of fame. It must have frustrated Daugherty to see critics praising his work by comparing it to Benton's. While the subject matter of their murals might have been similar, it was Daugherty who was more daring in his use of color. And it was Daugherty who might logically have been the American painter to bring the ideas of Matisse and the Delaunays into greater public consciousness. But some of these ideas must have been too daring for inclusion in publicly funded work of that era.

Murals

- Greenwich, Connecticut - Public Library: The Life and Times of General Israel Putnam

- Stamford, Connecticut - Ferguson Public Library: Untitled

- Stamford, Connecticut - Stamford Branch of the University of Connecticut, Jeremy Richard Library: School Activities

- Virden, Illinois - Post Office: Illinois Pastoral

References

- 25 Results for James Daugherty (1st Dibs).

- Daugherty, James Henry (1887-1974) (Connecticut State Library).

- Friends of James Daugherty Foundation (Friends of James Daugherty Foundation).

- Rebecca E. Lawton, Heroic America: James Daugherty's Mural Drawings from the 1930s, Resource Library June 23 (2005). Reprint of essay from the 1998 Art Center exhibit "James Daugherty's Mural Drawings from the 1930s"

- Wendy Watson, James Daugherty, Wendy Watson's Blog June 16 (2016).

- James Daugherty (Wikipedia).

- James Daugherty (Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center).

- James Daugherty – American Illustrator and Author 1889-1974 (Golden Age Illustrations Gallery).

- James Daugherty, Artist, Dead; Children's Book Author Was 84, New York Times February 22 (1974).

- James H. Daugherty (Forum Gallery).

- The Mayor’s Gallery presents New Deal artist James Daugherty (Hamlet Hub).