Biography

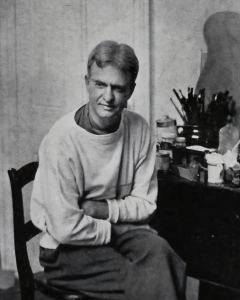

Few people are familiar with the name of painter James Ormsbee Chapin, except perhaps some hard-core fans of the late folksinger Harry Chapin (1942-1981), who was a grandson of James. Yet James Chapin may have been the single most influential painter in the development of the American Scene style that dominated federally-sponsored art in the 1930s. James was born in West Orange, NJ in 1887. He had a childhood stutter, which made him somewhat withdrawn, and he amused himself in the forests and rivers around his childhood home. He dropped out of high school at age 16 to take a job as a bank messenger in New York. He applied for drawing lessons at Cooper Union, but had to wait until he was 18 to enroll in evening classes in 1905. Subsequently he took evening classes in anatomical drawing from George Bridgman at the Art Students League, beginning in 1907.

Having earned a little money and, borrowing a bit from a relative, Chapin traveled to Antwerp, Belgium in 1910 to study at the Royal Academy. He did well there, earning several awards. Going to Paris, he discovered Cezanne and became a devoted follower for awhile. By 1912 he had run out of money and returned to New York, working as a textbook illustrator to pay off his debts. Chapin's work attracted the attention of the publishers Henry Holt & Company, and they engaged him to produce an illustrated edition of Robert Frost's North of Boston. He met Frost first in 1917, and the pair remained friends for 30 years, united by similarities in temperament and outlook.

In 1918 Chapin married Abby Beal Forbes, who had been his high school teacher. Their son James Forbes Chapin was born in 1919. He became a well-known jazz drummer and was eventually the father of Harry Chapin. James Chapin's marriage to Abby did not last more than a few years, and shortly after his divorce, Chapin's father and younger brother both died. While he succeeded in getting one-man shows at the New Gallery in New York in 1923 and 1924, they did not have a strong critical reception, and Chapin found himself depressed and broke.

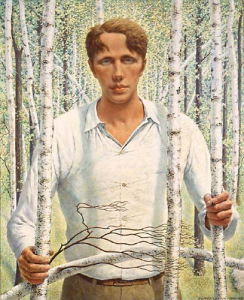

Influenced perhaps by Robert Frost, himself a disciple of Thoreau, Chapin sought a retreat in rural New Jersey. He rented a log cabin from the Marvin family. These were three siblings, great-grandchildren of Henry Marvin, who had owned several farms in the area in the first part of the 19th century. Living without electricity or running water, Chapin joined the Marvins in their daily chores. Within a year he had gained their friendship and confidence, and he began a series of paintings using them as his subjects. Deeply impressed by the humanity of his new friends, Chapin abandoned his previous artistic style and adopted an unflinchingly realistic approach in these paintings. This approach was to prove both popular and influential.

In 1925 Chapin had his third solo show at the New Gallery. This time his paintings had an impact. There followed shows at the Chicago Art Club in 1926 and the Frank Rehn Gallery in New York in 1927. Chapin received the Logan Prize from the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) in 1927 and the Temple Gold Medal from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). The AIC prize was for "Old Farm Hand" and the PAFA prize for "George Marvin and His Daughter Edith," both products of his time in rural New Jersey.

In 1928 Chapin painted "Ruby Green Singing," a portrait of a young black gospel singer in New York. This continued an interest that had started in New Jersey, one of creating insightful and sympathetic portraits of black Americans. This portrait was published in Harper's Magazine in 1929 and thus found its way onto the walls of many black households.

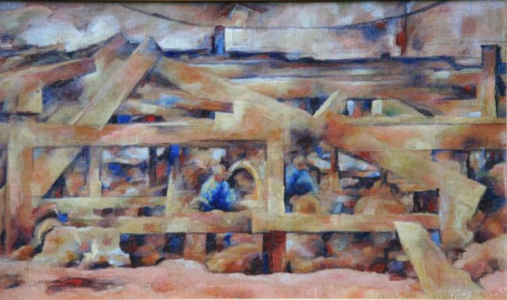

Chapin spent part of 1929 driving around New England, living in a laundry truck and looking for new subjects to paint. He returned to Manhattan for another solo exhibit at the Frank Rehn Gallery. There followed paintings of people from all phases of life in America - laborers, athletes, gangsters, blues singers, shop girls and the streets of New York's East Side. Chapin received the Popular Prize at the Pan-American Exhibition of Contemporary Art in Baltimore in 1931, and participated in the Art Competition at the 1932 Olympics as his popularity exploded nationwide. In 1932 alone he had 8 solo exhibits, and during the 1930s his work was in group shows in 20 museums.

Chapin began teaching one day a week at PAFA in 1935. Later in the decade he worked with Millard Sheets and taught in the Fine Arts Department of Claremont College in California. While in California he met Mary Fischer, whom he was to marry in 1941. James and Mary lived in New York for five years, after which they moved to New Jersey with their sons Elliot and Jed. During the 1940s Chapin supported his family with commercial commissions through Associated American Artists (AAA). Advertisements based upon Chapin's artwork were in wide circulation throughout the decade.

Chapin returned to portraiture in the 1950s - with commissions for several Time magazine covers. These included iconic portraits of Boris Pasternak, Thurgood Marshall, Edward Hopper, Jawaharlal Nehru and others - including, on June 20, 1960, "The Suburban Wife."

The 1960s, a time of intense political awareness in the United States, moved Chapin to strong political statements. His "A Medal for Johnny," for example, shows Lyndon Johnson and Hubert Humphrey holding up a bloody corpse, Johnson's hand drenched in the boy's blood. To escape the draft, Chapin's sons moved to Canada, and Chapin himself followed in 1969. He became a Canadian citizen shortly before his death in Toronto in 1975.

Critical Analysis

It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that James Chapin invented the American Scene. While Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton are the trio of painters most firmly connected with this style of art, Chapin's work preceded theirs by nearly a decade, and they were certainly influenced by it. Wood actually wrote the introduction to Chapin's 1940 AAA retrospective, effusively praising Chapin's work.

There's an interesting through line from Thoreau to Robert Frost to James Chapin - a particularly American line of descent, which is what made American Scene painting so popular in the Depression Era. It didn't hurt, of course, that there was also massive governmental support for this type of art in that period. In any case Chapin's paintings were typically free of the sentimentality that sometimes crept into the work of other American Scene painters. Chapin truly sympathized with his subjects and worked hard to portray them in all their humanity. This included their high points, when his subjects radiated the pleasure of success in simple daily pursuits, and the low points, when they may have slumped in drunken stupors.

While Chapin had 26 solo shows in the period 1926-1940, he had only two such shows between 1941 and 1975: a 1955 show at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton and a 1974 show at the Montclair Art Museum in Montclair, NJ. Following his death, there was a retrospective at the Yaneff Gallery in Toronto. The arc of Chapin's popularity tracked closely with the omnipresence of American Scene painting in the 1930s and 1940s and its near total disappearance with the rise of Abstract Expressionism in the postwar years. Chapin almost never ventured beyond realistic portrayals, despite his early interest in Cezanne. During his sojourn with the Marvin family, he had found something about humanity - his own, perhaps, as much as that of his subjects - and other topics no longer interested him as much.

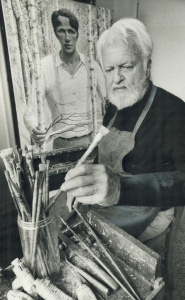

Chapin's portrait of Robert Frost, completed only a year before his death, has an interesting history. It was based, he said, on a drawing he had done in 1917, shortly after he had first met Frost. When he developed this painting in his later years, he found himself aging Frost backwards in time, so that the final portrait depicted Frost around 1905, more than a decade before Chapin had first met him. Perhaps this was a way of Chapin musing on his own life and on aging.

Murals

- Glen Ridge, New Jersey - Post Office: Glen Ridge

References

- Art for Every American Home: Associated Artists, 1934-2000 (Grey Art Museum).

- Arthur D. Hittner, Art of the Thirties, InCollect October 11 (2013).

- Larry Aydlette, Black History Month: The secret story behind a Florida museum’s beloved painting, Jacksonville.com | The Florida Times Union February 12 (2020).

- James Chapin (Olympedia).

- James Chapin (Art Cyclopedia). Has links to Time covers.

- James Chapin (RoGallery).

- James Chapin (1887 – 1975) (James Cox Gallery at Woodstock).

- James Chapin (1887-1975) Nine Workmen 1942 (Painting the American Scene).

- Michelle Vosper, James Chapin and the Marvin Farm, The Journal Late Spring (2024).

- James Ormsbee Chapin (askART).

- Sherman Reed Anderson, James Ormsbee Chapin and the Marvin Paintings: An Epic of the American Farm (2008).

- James Ormsbee Chapin Papers (Delaware Art Museum).

- James Ormsbee Chapin, "Amandini Caproni" or "Black Beret", 1912 (Ruby Lane).