Biography

Harry Donald Jones was born in Vincennes, IN. After training at Iowa University, Harvard and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, he moved to Iowa. Winning a prize for his painting submitted to the Iowa State Fair in 1932, he joined Grant Wood's mural team in 1933 to work on the Parks Library murals. Jones was never too happy with Wood's management style, which consisted of laying out the overall project and delegating the detail work to his younger and less prominent assistants. Jones claimed that his assignment amounted to nothing more than painting the bricks in panels on the library staircase.

A formal break with Wood occurred when Jones and Robert Francis White founded the Cooperative Mural Painters Group (CMP) in 1935. The group was successful in funding their proposal for an ambitious set of murals in Cedar Rapids, and Jones played a strong role in the design of this work.

In 1936 Jones and White attended the first meeting of the American Artists' Congress (AAC) in New York. In later years Jones said that the AAC had been too far left for his taste, but this might have been more a reflection of the virulent anti-Communist mood of 1950s America than an accurate portrayal of Jones's youthful impulses.

The Cedar Rapids murals occupied Jones from 1935-1937. In 1936 his painting "Country Gasoline Station" was accepted by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The subject matter was a conscious rejection of the Grant Wood agrarian ethic. And Jones publicly defied Wood by saying this work as “painted without inspirational aid of milking cows, the recently published recipe for midwestern ideas.” This crack stemmed from Wood's claim to have had his greatest inspiration while milking a cow.

Despite Jones's thumbing his nose at the powers that be, he was appointed to supervise the Iowa Index of American Design from 1937-1939. And in the years 1939-1941 he succeeded White as the Iowa state director for the Federal Arts Project. During the period 1937-1941 Jones completed a large mural for the Des Moines Public Library entitled "A Social History of Des Moines." That mural is still on display in what is now the home of the World Food Prize.

Jones served in the U.S. Navy during World War II. After the war, in 1946, he moved to San Francisco, where he began a successful career in photography. He continued to paint, more in a surrealistic or abstract geometric mode. He died in Salt Lake City in 1995.

Critical Analysis

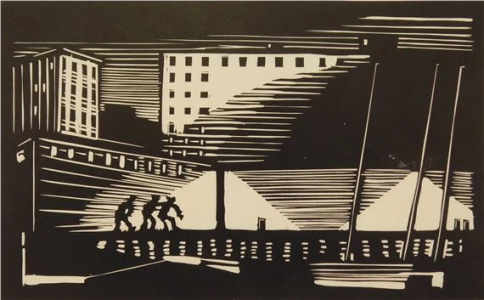

Despite Jones's later denials, he was one of the more political painters of his era. Having studied the works of the Mexican muralists, he believed in art as an instrument of revolution and was not shy about including political messages in his paintings. His woodblock prints from the 1930s are classics of that genre. And his contributions to the Cedar Rapids project are interesting as much for their content as their artistic merit. One section of the mural on the east wall deals with the eradication of venereal disease - a topic that was not discussed in polite company in that era, no matter how pressing the need to deal with it. And the south wall of the Cedar Rapids courtroom was taken up with Jones's depiction of the historical contributions of South American culture. To the left Jones portrayed José Clement Orozco painting his figure of Christ in Orozco's Dartmouth College murals. And to the right he showed archeological excavations of ancient sites in South America.

It is striking that Jones could challenge as prominent a figure as Wood and paint explicit political messages at a time when federal project managers were very nervous about public reactions to the projects they funded. Of course the Cedar Rapids murals did end up getting painted over - more than once - but they are now fully restored and an inspiring testament to the ultimate triumph of free speech.

Murals

- Cedar Rapids, Iowa - City Hall: Archeological Research

- Cedar Rapids, Iowa - City Hall: Vigilante Justice, Witchcraft, Modern Medicine

- Des Moines, Iowa - World Food Prize Hall of Laureates: A Social History of Des Moines

References

- Biography of Harry Donald Jones (artprice).

- Federal Courthouse Mural (Cedar Rapids).

- Harry Donald Jones (Greater Des Moines Public Art Foundation).

- Breanne Robertson, Politics in Paint: The Creation, Destruction, and Restoration of the Cedar Rapids Federal Courthouse Mural, The Annals of Iowa Volume 74, Number 3 (Summer 2015) (2015).

- A Social History of Des Moines (Greater Des Moines Public Art Foundation).