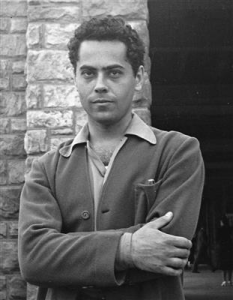

Biography

Harold Lehman was solidly in the center of the art world in the 1930s and 1940s, and pursued a lifelong career in the field of art. But he never achieved the level of fame accorded to some of his closest friends and his work is not familiar to most people today. Lehman was born in 1913 to Jewish immigrants. His mother was a seamstress, and his father struggled to find suitable employment, eventually abandoning the family and moving to California, where he found work as an insurance agent. Harold's mother could not support the children by herself, so Harold and two of his brothers grew up in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum.

Lehman's introduction to art came from classes in school and from programs in a summer camp. Having learned sculptural technique from a camp counselor, Lehman sculpted copies of plaster casts on his own initiative. He also had an interest in music, playing the harmonica on a radio broadcast at one point.

In 1930, having aged out of the orphanage, Lehman moved to California to rejoin his father. Almost immediately, he enrolled in Manual Arts High School, where he met like-minded young artists Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston and Manuel Tolegian. This quartet led a somewhat madcap existence, remaining in school only by virtue of their artistic excellence. A fifth friend to this group was Reuben Kadish, who had attended another high school before being expelled for his political activity.

Lehman graduated from Manual Arts in 1931 and won an award at the Los Angeles Museum of art for his sculpture "The Prophet Jeremiah." From 1931-1932 he attended the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles on a sculpture scholarship, where he worked on stone carvings, among other things. In 1932 David Siqueiros came to the Chouinard Art Institute to teach fresco. Lehman met Siqueiros at a public lecture, and Lehman and his friends were able to watch Siqueiros paint his outdoor mural "Tropical America." Lehman started taking lessons from Siqueiros, paying him by working as an assistant. Conservative Los Angeles could not tolerate the political radicalism of Siqueiros, and the frescoes that Siqueiros and his followers were creating were destroyed in a raid by the Los Angeles police.

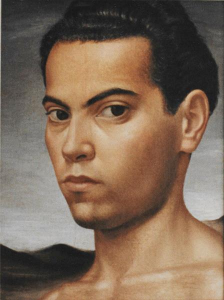

Lacking facilities to do sculpture on his own, Lehman turned to painting. His portrait "The Landlady" won second prize at the Los Angeles Museum's 14th Annual Exhibit. Lehman and Guston had a two-man show at the Stanley Rose Gallery in 1933. Guston, Lehman and Kadish attempted a PWAP mural for the Frank Riggins Trade School, but their effort was unsuccessul, and the project was turned over to another artist, Leo Katz.

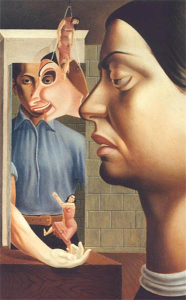

Salvador Dali's first American exhibition was in 1934. An American response to European Surrealism was developed by the "Post-Surrealists" Lorser Feitelson and Helon Lundeberg. Lehman joined these artists briefly, but by the time of his one-man show at the Jake Zeitlin Gallery in Los Angeles (1935), he had fallen out with Feitelson, regarding the movement as too shallow. Meanwhile Lehman's girlfriend, the dancer Thelma Babbit (portrayed in Lehman's "Portrait of the Dancer Plus Sculptor"), had moved to New York to work with Martha Graham. Lehman felt that he had exhausted the possibilities of Southern California and headed back to New York himself. As he proudly noted many years later, in his five years in California he had gone from being an obscure high school student to inclusion of a listing in Who's Who in Art in the inaugural issue of Who's Who Magazine.

In New York, Lehman had his second opportunity to work with Siqueiros, who was organizing a workshop where artists could come to understand modern industrial materials. Lehman recruited his friend Pollock to join the workshop and credits Siqueiros's experiments with dripping automotive lacquers and seeing how they spread on a surface with Pollock's later famous drip painting style.

Siqueiros went to Spain in 1937, but his workshop continued in New York. Lehman was involved with the Artists Union and, from 1937-1940, with the Federal Art Project. From 1938-1940 he worked on a massive mural "Man's Daily Bread" for the cafeteria at the Rikers Island prison. Only fragments of this work remain after a prison warden deemed the work unsuitable and had it destroyed. Lehman also received a commission for a Post Office mural in Renovo, PA, completed in 1943 and titled "Locomotive Repair Operation."

Lehman worked on a float for a Mayday parade in 1941. When he was called up for his army physical, he had just fallen off of a ladder and broken both arms. He argued for a deferment - not because of his injury, but because he was opposed to violence and felt that his work was already having an impact on the war effort. He moved to Woodstock, NY for the period 1942-1946 and produced paintings that were used to make War Bonds posters for the Treasury Department. He also made paintings with war themes and put on exhibits at the Woodstock Art Association Gallery. His works "Deliver Us From Evil" and "This Is the Enemy" were chosen for display at an exhibit of war posters at the Museum of Modern Art.

Following the war, Lehman did easel painting, sculpture and photography. He also began teaching from his New York studio. From 1950 on Lehman worked as a scenic artist and designer for large-scale theme parks, television and film. He married a student of his, Leona Koutras, in 1955 and moved to New Jersey to raise his two children.

The 1960s brought work at theme parks Asbury Park and Freedom Land. He designed the Coca-Cola Pavilion for the New York World's Fair in 1964 and was a design consultant for Expo '67 in Montreal. In the 1970s Lehman became a designer and scenic artist for CBS television. He had one-man shows of his art at Farleigh Dickinson University but never ventured into Abstract Expressionism.

Three of Lehman's surrealist paintings were included in a 1995 exhibit "Pacific Dreams." Always interested in new possibilities for making art, Lehman taught himself Photoshop and Illustrator in his 80s and used them to generate digital images. He died in Leonia, NJ in 2006 at age 93.

Critical Analysis

Lehman's "Locomotive Repair Operation" is perhaps the most compelling of the Post Office murals in Pennsylvania. The scene is in the workyard of the repair facility. In the center of the mural three men are operating a crane to lift a massive rim from a locomotive wheel. To the right stands a workman ready at an acetylene valve, and to the left there is another workman tending to a valve and a foreman holding a famous wartime poster by Jean Carlu.

What makes this work compelling is its unusual combination of scope and detail. Lehman shows the entirety of the repair facility - its brick walls, a large shed, and the hills of the Renovo area accurately represented in the background. But at the same time Lehman depicts a human component of the work - in the form of the workmen intently focused on their various tasks. And that touch of humanity is brought home in various details - some too minor to be noticed at first. The workmen all have union buttons in their caps - a detail that would have been censored out of the painting had the administrators in Washington noticed them. And, similarly, there are detail in every portion of the painting - from the ornamental brickwork on the wall to the left to the lettered markings on each of the rims to the chimneys in the background, one of which is today's only remnant of the Renovo facility.

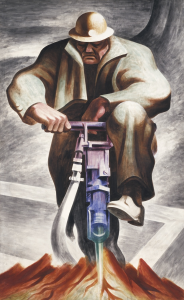

The fragment of Lehman's Rikers Island mural that survives in the Smithsonian American Art Museum (known as "The Driller") is compelling for similar reasons. The bulky figure of the workman grabs one's attention immediately. But it is the details of the work that keep one looking at the work. There is the interesting range of colors used to depict the drill and the remarkable posture of the workman, which Lehman insists was a precise representation of how a workman would control such a heavy piece of machinery. Lehman was also proud of the brown and green shading he used on the workman's clothing, noting that Michelangelo had used a similar technique. There are no union buttons in this painting, but it exudes an unmistakable air of power and hard work.

Murals

- Renovo, Pennsylvania - Post Office: Locomotive Repair Operation

References

- Harold Lehman (askART).

- Harold Lehman (Wikipedia).

- Harold Lehman - Biography (Harold Lehman).

- Harold Lehman photograph collection (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

- Oral history interview with Harold Lehman, 1997 Mar. 28 (Archives of American Art).