Biography

Frederick Charles "Fritz" Fuglister was a pivotal figure in the development of modern oceanography. This was not, it should be noted, the result of a childhood ambition, although his natural inclinations may have made him well-suited to this career. Rather, Fuglister had hoped to become an artist and a musician and detoured into oceanography quite by accident. Nonetheless his artistic skills were likely essential for his success in oceanography, and he retained his enthusiasm for music and art all his life.

Fuglister was born in New York, NY in 1909, the child of Swiss immigrants. After graduation from high school in 1927 he took day classes at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC for two years while working nights as an elevator operator and watchman. He simultaneously continued his lessons on the violin and cello.

In 1929 Fuglister rode his motorcycle to Provincetown, MA to soak up the atmosphere of the artists community thriving there. He returned to Washington to help run an artists' club and gallery with some friends there. He was back in Provincetown in 1931, taking classes with E. Ambrose Webster. Webster was a pioneering teacher of modernism. He had fallen in love with the light on Cape Cod, and he was a formalist in his teaching, saying "Painting should be taught like mathematics, as a science. You can't teach talent or inspiration but you can teach painting." He emphasized pattern, rhythm and geometry as important means in artistic design - just the prescription a man of Fuglister's inclinations would embrace.

His mother's ill health forced a return to Washington in 1932. With the onset of the Depression, Fuglister received a commission to paint the panels "Music" and "Drama" for Eastern High School in DC in 1934. But a year later he was back in Provincetown, living in an improvised shack, painting and playing his violin. In 1937 he received a commission to paint a mural for the Falmouth, MA Police Station. At the Falmouth Public Library he met the reference librarian Cecelia Bowerman, whom he married in 1939.

Fuglister's major Depression Era work was a massive project for the Brockton, MA Public Library on "A History of Books and Printing" (1941). His mural covered the four walls of a gorgeous rotunda in the Library and was restored to its original beauty in 2003. While Fuglister was working on this project, a fateful incident occurred. He was at a stage in his work where he had to pause his painting briefly while a new section of the rotunda wall was being prepared for painting. At this point a friend suggested that he might enjoy a three-week cruise to Georges Bank on an oceanographic vessel operating out of Woods Hole, MA.

Fuglister enjoyed his voyage and returned to Brockton to finish his mural. He applied for a mural commission in New Bedford, MA but was rejected. Meanwhile Woods Hole offered him a job - this time with an actual salary - and he jumped at the chance. His new job found him onboard a ship using an instrument called a bathythermograph (BT) that measured temperatures in the ocean depths. Fuglister's job was to launch the BT again and again, and to record the measurements it made.

The U.S. Navy was interested in the thermal profile of the ocean because submarines could successfully hide beneath layers of warm water. This assured steady funding for the research at Woods Hole. Back ashore, Fuglister was busy logging the measurements he had made onboard the ship. And he was tasked to train Navy personnel to use the BT when wartime activities made it too hazardous for civilians to take the BT out on a cruise.

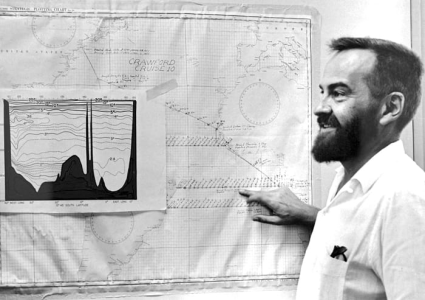

The director of Woods Hole, Columbus Iselin, asked Fuglister to display the BT data on ocean charts, and this is where Fuglister's artistic training and eye for patterns all came into play. As he worked to display the BT data, he began to see structures in the Gulf Stream that nobody had previously noticed. Rather than a smooth steady current the Gulf Stream was more like a meandering river, with various eddies constantly spinning off to the side. Sometimes these eddies would detach the form circular cores that trapped warm or cool water. These hot cores and cold cores were found to transport water across the main stream.

Fuglister's visualization of the Gulf Stream currents came to be regarded as an uncanny display of scientific intuition and revolutionized aspects of oceanography. In 1950 Fuglister directed a multi-ship survey of the Gulf Stream known as Operation Cabot. He worked on the International Geophysical Year in the late 1950s and directed a second multi-ship survey, Gulf Stream 60, in 1960. His prominence in the field was recognized when he was named head of the oceanography department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute from 1962-1967. Between 1965 and 1967 he took 16 cruises to study cold-core rings. His work won him the Agassiz Medal of the National Academy of Sciences for "stimulating and successful observations of the Gulf Stream and its vortices." His colleagues called him "the private biographer of the Gulf Stream."

Even as he gained prominence in the world of oceanography Fuglister continued to paint and play music, albeit strictly as an amateur practitioner. He did help out with the painting of murals at the Provincetown High School in 1947. And privately he explored many styles of art, showing the same curiosity that worked so well for him in the world of science.

Critical Analysis

Since Fuglister did not pursue a professional career in art once he was working at Woods Hole, there is not a large body of work from which to judge his artistic career. What is clear, however, is that Fuglister brought an artist's sensibility to a field of science that was in need of some organizational principle. And Fuglister was able to provide that principle, effectively painting and repainting pictures of the Gulf Stream in the charts he created to describe the Gulf Stream's structure.

His continuing efforts in fine art showed the same curiosity that had allowed him to make breakthroughs in oceanography. He worked in many different styles, and, late in his career, he started to paint on non-rectangular canvases, carefully constructed with five or seven sides. He seemed always to be looking for something new, always eager to encounter the unexpected.

The same curiosity drove his love for music. He and Cecelia played in orchestras across Cape Cod, and they often convened groups of musicians to play chamber music at their home. Fritz particularly liked sight reading, where the musicians would take an unfamiliar piece of music just to see how it would all come together. Much as he had successfully plumbed the depths of the ocean to see what structure he might find, he would explore music and art with the same boundless curiosity and love for the harmony and order he hoped to find.

Murals

- Brockton, Massachusetts - Public Library: A History of Books and Printing

References

- 12 Winslow Street (Building Provincetown). Provincetown High School.

- The Art, Music and Oceanography of Fritz Fuglister (Woods Hole Museum). By Jennifer Stone Gaines and Anne D. Halpin.

- Eastern High School.National Register of Historic Places Nomination (2023).

- Three-Part Retrospective on Fritz Fuglister: His Art, Music and Oceanography. Video with running time of 11:36.

- Rich Holmes, Woods Hole: Where Science and Art Merge, Cape Cod Magazine October (2015). p.70.