Biography

Ethel Magafan and her twin sister Jenne were born in Chicago, IL in 1916. Their parents were immigrants - the father from Greece and the mother from Poland. In 1919 the family moved to Colorado Springs, CO for the father's health. He worked as a waiter there until 1930, when he got a job as head waiter at a hotel in Denver. The twins were recognized for their artistic abilities as early as junior high school, and their father encouraged them to develop their talent. Sadly, he died in 1932, putting the family in severe financial straits.

The twins, however, continued to prosper in terms of their artistic development. They had the good fortune to encounter a terrific art teacher at East High School in Denver. Helen Perry had studied at the Art Institute in Chicago and with Andre Lhoté in Paris, so she had an unusual background for a high school art teacher. She introduced her students not only to the European masters such as Matisse, Picasso and Cézanne, but she also invited local artists to speak to her art classes. Thus Ethel and Jenne became acquainted with the muralist Frank Mechau and the architect Jacques Benedict. Remarkably, Perry's students included five who became nationally known artists. In addition to the Magafan twins, Edward Chavez, Bernard Arnest and Eugene Trentham were all students of hers at East High.

In 1933-1934 Ethel won a scholarship to the Kirkland School of Art in Denver. And Helen Perry covered the tuition for Ethel and Jenne at Mechau's School of Art in 1933-1934. The twins apprenticed with Mechau in 1934 and again in 1936. They also worked as fashion artists at a Denver department store. In 1936, Jenne won the Carter Memorial Art Scholarship, as had a number of Perry's other students previously done. Jenne shared her award with Ethel, allowing them both to enroll at the Broadmoor Art Academy in Colorado Springs (soon to be renamed the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center). Their teachers in Colorado Springs included Frank Mechau, Boardman Robinson and Peppino Mangravite. When their meager scholarship funds ran out, Mechau hired the twins as his assistants. Thus they learned the techniques of mural painting and the studied the compositional models of the Renaissance masters. Mangravite hired Ethel and Jenne to assist him on his commission for a Post Office mural in Atlantic City, NJ.

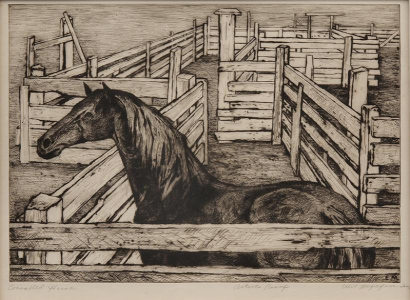

Ethel and Jenne each had seven commissions for government murals. Ethel's first effort was unsuccessful, her proposal "Lawrence Massacre" for Fort Scott, KS (1937). As the title suggests, her idea was too strong to be accepted. Actually the rejection came not from the federal government but from the local citizenry, who preferred to forget this horrific incident from their past. Another 1937 murals - "Indian Dance" for the U.S. Senate - was successfully completed but has unfortunately been lost. In 1938 Ethel became the youngest artist to complete a Post Office mural with her "Threshing" for Auburn, NE. Her solidly regional composition was a hit with the local audience. This success led to three other Post Office murals: "Cotton Pickers" for Wynne, AR (1940), "Prairie Fire" for Madill, OK (1941), and "The Horse Corral" for South Denver, CO (1942). Collaborating with Jenne, she completed "Mountains in Snow" for the Social Security Building in 1942. Her seventh federal mural was for the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, entitled "The Battle of New Orleans" (1942).

Ethel had her first solo exhibition at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in New York in 1940. Jenne had become romantically involved with Edward Chavez by this time, and he and the twins moved around the country together when Chavez received a military commission. Thus they lived in Los Angeles from 1941-1942, moved briefly to Cheyenne, WY and then returned to Los Angeles in 1943-1944. While in Southern California the twins executed a floral mural for the Beverly Hills Hotel and painted ocean scenes that were exhibited at the Raymond Galleries in Beverly Hills.

During this period they met the artist couple Arnold Blanch and Doris Lee (former teachers in Colorado Springs) who recommended Woodstock, NY as the ideal artist's residence. The novelist Irving Stone and the painter Fletcher Martin also had good words for Woodstock, so Ethel, Jenne and Edward drove to Woodstock in 1945 and took up residence there. In 1946 Ethel married the artist and musician Bruce Currie. Jenne also married Edward once settled in Woodstock.

Ethel and Bruce purchased a barn outside of Woodstock for their home and studios. This would be the first time Ethel had worked independently of Jenne. Even as Ethel transitioned from the Regionalist style that had served her so well in her government work, she received many awards for her painting. She won a Stacey Scholarship in 1947, a Tiffany Fellowship in 1949 and a Fulbright for 1951-1952. The Fulbright allowed her to travel to Greece, while Jenne and Edward traveled to Italy on his Fulbright. Tragically, Jenne died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage shortly after returning to the United States. Ethel said that she never got over this event and named her daughter Jenne Magafan Currie (b.1956) in memory of her sister.

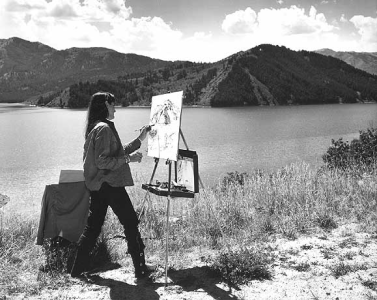

Ethel received the Benjamin Altman Landscape Prize from the National Academy of Design in 1955. She was elected as a full Academician of the National Academy in 1968. Starting around 1956, she and Bruce would take annual trips to Colorado for continued inspiration from the natural environment there. Recognizing her keen interest in the subject, the U.S. Department of Interior hired Ethel in 1971 to document the development and conservation of water resources in the West. Her sketches for this project were shown in an exhibit at the National Gallery of Art and taken on a national tour sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution.

Ethel's late career had some interesting twists and turns. She was an Artist in Residence at Syracuse University and at the University of Georgia in Athens, GA in 1970. She received a mural commission for "Grant in the Wilderness" (1979), installed at the Fredericksburg National Memorial Military Park in Chancellorsville, VA. And, after her cartoon for the "Lawrence Massacre" mural was exhibited in 1987, a private collector commissioned her to complete the mural, now displayed in the Watkins Museum of History in Lawrence, KS. Ethel died in Woodstock in 1993.

Critical Analysis

Ethel Magafan's career had two phases, as with many artists who flourished in Depression Era government programs. The first phase was her Regionalist period and included all of her mural compositions. She and her twin sister Jenne were among the most prolific of the Depression Era muralists, with seven commissions each. During Jenne's brief lifetime, she and Ethel had seven joint exhibits of their artwork.

Ethel's murals were skillfully executed and - within the limits of the sponsoring program - included elements that underscored her own social consciousness. It's likely that this bent was the result of her being part of an immigrant family and perhaps feeling out of place in the Denver community where she went to high school. But the central role that art played in that community provided a strong foundation for her whole career and allowed her some degree of independence in her art and the courage to express her viewpoint through this art.

A striking example of this is Ethel's mural for Wynne, AR. As Steve Frangos points out, "Cotton Pickers" portrays a group of workers busily engaged in various stages of cotton production. Unlike murals that emphasized white dominance, this mural has no white overseers, in fact no white people at all. Furthermore, the central figure in the mural was modeled on Marian Anderson, who had performed in front of the Lincoln Memorial in her famous Washington concerts the year before Ethel painted her mural. It was a daring choice, but subtle enough to have been missed by the white power structure in Arkansas. It showed how Ethel could appease the powers that be without ever knuckling under to their dictates.

The second phase of Ethel's career came after the Depression was over. True to her roots in Colorado, she evolved a semi-abstract style of landscape painting, characterized by bright pigments, thickly applied to the canvas. Like her earlier work, these paintings were well-received. In addition to the many awards that Ethel received, she held 19 solo exhibitions in the years 1962-1993.

Murals

- Wynne, Arkansas - Post Office: Cotton Pickers

- Denver, Colorado - South Denver Station Post Office: The Horse Corral

- Washington, District of Columbia - Department of Health and Human Services: Mountains in the Snow

- Washington, District of Columbia - Recorder of Deeds Building: The Battle of New Orleans

- Washington, District of Columbia - Recorder of Deeds Building: The Battle of New Orleans

- Auburn, Nebraska - Post Office: Threshing

- Madill, Oklahoma - Post Office: Prairie Fire

References

- Ethel Magafan (Museum of Nebraska Art).

- Ethel Magafan (1916-1993) (David Cook Galleries).

- Ethel Magafan (1916-1993) (Sullvan Goss).

- Ethel Magafan Dead; Landscape Painter, 76, New York Times April 29 (1993).

- Steve Frangos, The Twined Muses: Ethel and Jenne Magafan, Pella Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 31.2 (2005) (2005).