Biography

Elizabeth Lochrie was born on the American frontier in Deer Lodge, Montana. As a child she mingled freely with Cree people in nearby settlements, playing with children there and learning their sign language. At age 12, her father was murdered by a drunken teenager after reprimanding the boy for cursing in front of ladies. Her father Arthur had been an outdoorsman and photographer, encouraging Elizabeth to ride bareback at an early age and encouraging her adventurous pursuits. Notably, Arthur helped support the Cree in Deer Lodge Valley, and his photographs of the Cree remain in the possession of the Montana Historical Society.

After her father's death, Elizabeth and her mother moved to Butte, where her early interest in art was reinforced with instruction from landscape painter Vanna Owings Webb. Lochrie attended the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, graduating in 1911. Back West, she studied with Winold Reiss, who had been hired by the Great Northern Railway to promote Glacier National Park as a tourist destination. She also traveled to San Francisco, where she studied with Dorothy Puccinelli and Victor Arnautoff.

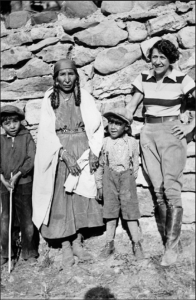

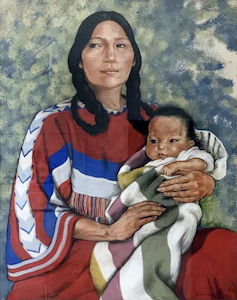

Returning to Montana, Lochrie painted a suite of 18 children's murals for the Montana State Hospital in Galen. Around this time she began to focus on the portrayal of Native Americans people and customs, using her fluency in native languages and her obvious empathy to gain an unusual entree to Native American settlements. From 1931 on she specialized in portraits of Native American people. Her friendship with Gypsy Bull Child, whose husband was the Blackfeet Chief George Bull Child, gave her increased intimacy with the Blackfeet people, and in 1932 she was adopted by the Blackfeet Nation.

Lochrie's marriage in 1913 to Arthur Lochrie, a Butte banker, gave her considerable freedom of movement, particularly since her husband supported her artistic efforts. Elizabeth would drive her Cadillac, laden with art supplies, across the most remote roads of Montana, traveling alone as she sought out subjects for new paintings. She signed her work "E. Lochrie" to avoid the stigma then attached to female artists. Her Blackfeet friends admired her fierce independence and gave her the name "Netchitaki," meaning "Woman Alone in Her Way."

Lochrie worked as a staff artist for the Great Northern Railway from 1936-1939. She received three commissions for Post Office murals in Montana and Idaho. She continued to visit Blackfeet communities every summer until late in life, when she moved to Ojai, California, where she died in 1981. She left behind a vast body of work, helping to preserve the culture and traditions of the Native American people she loved so well.

Critical Analysis

Lochrie's work shows great technical mastery, comparable to that of other artists who specialized in the portraiture of Native American people such as Winold Reiss himself. She used her talent both to showcase the strength and dignity of her subjects and to document the dress, customs and traditions of the Blackfeet Nation. Her work became a touchstone and reference for others who honored these traditions.

Murals

- Burley, Idaho - Post Office: Pioneers on the Oregon Trail Along the Snake River

- Saint Anthony, Idaho - Post Office: The Fur Traders

- Dillon, Montana - Post Office: News from the States

References

- Elizabeth Davey Lochrie (Hockaday Museum of Art).

- Elizabeth Davey Lochrie (Montana Historical Society).

- M.R.N., Elizabeth Lochrie (1890 – 1981), American Gallery January 8 (2011).

- A Half-Century of Paintings By Elizabeth Lochrie (Elizabeth Lochrie).

- A Half-Century of Paintings by Elizabeth Lochrie (Elizabeth Davie Lochrie). 1992 article by Betty Lochrie Hoag McGlynn, Elizabeth Lochrie's daughter.

- Lochrie (Montana Historical Society). Lochrie paintings at the Montana Historical Society.

- Elizabeth Joan Mentzer, Made in Montana : Montana's post office murals (1989).

- Elizabeth Mentzer, Made in Montana: Montana's Post Office Murals, Montana: The Magazine of Western History Volume 53 Number 3 (Autumn 2003), pp 44-53 (2003). Gives dimensions of the Leo Beaulaurier mural in Billings as 161"x43.5", or an aspect ratio of 3.70:1. Small B/W photograph of the Verona Burkhard mural in Deer Lodge has an aspect ratio of 2.56:1.

- Erika Fredrickson, A Work of Art, Montanan Winter (2015). Page 16