Biography

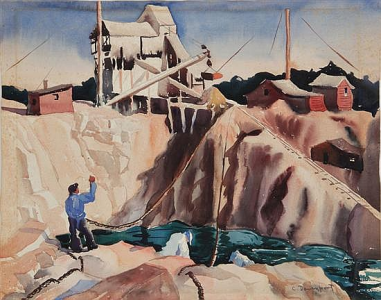

Carson Sutherlin Davenport was born in 1908 in Danville, VA, the son of a railroad engineer. He attended the Danville public schools and enrolled in an art course at Stratford College in Danville in 1929. He attended the Parsons School of Design on scholarship and studied in the Grand Central School of Art's Summer Program in Maine in the summer of 1929. He attended the Corcoran School in Washington in 1929-1930, winning the second prize for antique figure drawing. He was back in Maine in the summer of 1932. The same year his work was shown in a group show of the Art League in Washington, DC. And he received a grant that enabled him to work at the John Ringling School of Art in Sarasota, FL.

When the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) began in 1933, Davenport was chosen to illustrate Civil Works Administration projects in Danville. He exhibited at the PWAP National Exhibition of Art at the Corcoran Gallery in 1934, where his watercolor "Pioneer Women" was selected for display in the White House. The Treasury Department hired Davenport to illustrate the industries of Virginia with watercolors and etchings in 1936, and his work was shown by the Washington Watercolor Club at the Corcoran in 1936 and at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1937.

In the years 1937-1938 Davenport served as director of the WPA Art School and Gallery at Big Stone Gap, VA. The Treasury Department hired Davenport to illustrate the industries of Virginia with watercolors and etchings in 1936, and his work was shown by the Washington Watercolor Club at the Corcoran in 1936 and at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1937.

In the years 1937-1938 Davenport served as director of the WPA Art School and Gallery at Big Stone Gap, VA. He opened his own studio in Danville in 1938. The same year he completed a Post Office mural "Harvest Season in Southern Virginia" for Chatham, VA. In 1939 he exhibited at the International Watercolor Exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. He also completed two murals for the Greensboro, GA Post Office, "Cotton Picking in Georgia" and "The Burning of Greensborough." A capstone of Davenport's career in the 1930s was the selection of his art for the 1939 New York World's Fair.

In 1940 Davenport was named to a senior fellowship and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and given a solo exhibition of 42 oils and watercolors at the museum. In 1943 he was named chair of the Art Department at Averett College with a mandate to emphasize commercial art. He remained in that position until his retirement in 1969, with the exception of the year 1945, which he spent in New York.

Davenport fulfilled a long-standing ambition in 1960 with the establishment of a summer art school on Chincoteague Island in Virginia, where he painted many pictures of the wild ponies that resided there and of local marine landscapes. By 1964 he had transformed the Chincoteague school into a summer art gallery. Davenport died in Danville in 1972.

Critical Analysis

Carson Davenport completed three Post Office murals, and there exist sketches of several other proposed murals. All of these compositions are skillfully put together and successfully engage the viewer. Davenport was a stickler for his compositions, insisting that dominant female figure in "Harvest Season in Southern Virginia" be retained, arguing that, although it was out of scale with the rest of the painting, it provided a key decorative element.

While Davenport's mural sketches and his harvest mural in Chatham, VA all have non-controversial subjects, his Greensboro, GA murals did run into a lot of trouble. When Davenport visited Greensboro, he encountered a faction of local politicians and an amateur historian who vociferously advocated for a depiction of an alleged massacre by Native Americans. Davenport himself was inclined toward a more peaceful scene - an inclination backed up by the administrators in Washington. So it came to be that the first of two murals in the Greensboro Post Office depicted a scene in the local cotton fields. Unappeased, the Greensboro townspeople demanded their massacre. Washington relented, and Davenport didn't mind getting paid twice for one Post Office site. He provided as gory a scene as the most virulent racist in the community might have wanted.

Move forward now a few decades. In recent years the Postal Service has been wrapping "controversial" murals in black plastic, hiding them from view and probably damaging them irreparably. Which Greensboro mural received this treatment? Not the violent scene celebrating genocide of the Native American population; the cotton field simply had to go. It's hard to understand the logic of this choice, even if you accept the idea of censoring art previously approved by the community. Southerners are often reluctant to admit that their communities were built on an economy of slave-holders, so anything that reminds people of this historical fact can make them squirm. And some black people are sensitive to stereotypical depictions. The Postal Service, to its credit, provides a history of "The Burning of Greensborough," but, to its shame, it is allowing the destruction of "Cotton Picking in Georgia."

Davenport's murals and his early easel painting were straightforward regionalist representational works. But in his later paintings he aimed for a style that, as he put it would "stimulate the brilliance of the color of mosaic, as Roualt was influenced by the brilliance of the colors of stained glass." An example of his use of color is given by "Chincoteague Ponies #1" (1956), one of many paintings involving scenes on Chincoteague Island. A later work, "Surfers at Chincoteague Island Beach" (1968), may have been aimed at tourists visiting his Chincoteague gallery but also displays some adventurous use of color.

Murals

- Greensboro, Georgia - Post Office: Cotton Picking in Georgia

- Greensboro, Georgia - Post Office: The Burning of Greensborough

- Chatham, Virginia - Post Office: Harvest Season in Southern Virginia

References

- The Burning of Greensborough (Indians at the Post Office). Commentary by Denise Neil-Binion, Delaware/Cherokee Nation.

- Carson Davenport (Danville Museum of Fine Arts & History).

- Carson Sutherlin Davenport (Library of Virginia).

- Carson Sutherlin Davenport (askART).

- Herman E. Melton, Chatham Post Office Mural Depicts Southern Harvest, Star-Tribune March 21 (2001).

- Danville Hall of Fame (Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History).