Biography

Carlos Lopez was born in Cuba to Spanish parents. His early childhood was spent in the Asturias region of Spain, where he explored some of the caves later made famous for their prehistoric art. This was Lopez's first introduction to art. The family emigrated to the United States in 1919. Lopez worked briefly at Ford's River Rouge Plant in Detroit before spending a year at the Art Institute of Chicago. He studied at the Detroit Art Academy from 1930 to 1933, where he met his wife, Rhoda LeBlanc. By 1933 he had become a director of The Art Academy, a post he held until 1937.

In 1937 his painting "Spring" won the Friends of Modern Art Prize at the Detroit Insitute of Arts, one of dozens of such prizes that he garnered during his career. From 1937-1942 he taught at the Meinzinger Art School of Detroit. During this period he received five mural commissions - four for Post Offices in Michigan and Illinois and one for a painting in the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington.

He was hired by the War Department in 1943, first to portray industry preparing for the War and then to follow the troops in Africa. Funding for the latter position dried up, and Lopez became a war correspondent for Life Magazine.

Following the War, Lopez was hired to teach art at the University of Michigan School of Art and Design. He and his wife also taught in summer school sessions in Saugatuck, Michigan. He became known as one of the pre-eminent painters of Michigan, participating in exhibitions such as "Michigan on Canvas" in 1946, and he regularly won prizes in state and national competitions. But, saddled with ill health from a childhood attack of rheumatic fever, he died prematurely in 1953.

Critical Analysis

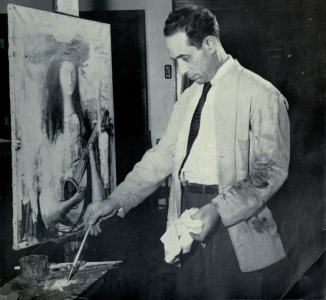

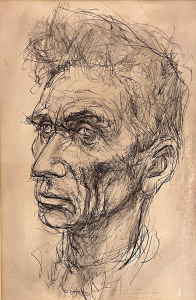

After his wartime work in Africa, Lopez returned to the United States to paint "things I really know something about." This meant regional landscapes or human figures. Although most of his work was in the style of the American Scene, his later paintings suggest an evolution to a more expressionist style. He was an excellent draftsman, and his paintings show a bold use of brushwork and color.

A biography of Lopez cannot ignore the fact of his Hispanic origins and the role they played in his public reception. His mural for Birmingham, Michigan met with outright hostility from a small minority of Birmingham residents. Fortunately, Lopez had his champions in the local press, and the criticism did not impede work. The critics claimed that Lopez's figures didn't look "American," although Lopez was able to cite the models for a dozen on the people in his mural and point to their photographs in historical records. Other figures in his mural were based on contemporary sketches that his wife had made in Birmingham. It's clear that the critics were expressing the racist sentiment of the time and not any valid artistic complaints.

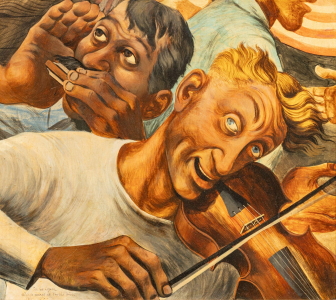

Interestingly, while the Birmingham mural depicted solid white citizens of historical Birmingham, Lopez's mural for the Recorder of Deeds Building went in a different historical direction. That mural shows African American soldiers in action in the Civil War. It provided an unusually sympathetic rendering of one aspect of the Black experience in that era, one that might not have been appreciated in Birmingham but was celebrated in the Washington of Franklin Roosevelt.

Murals

- Washington, District of Columbia - Recorder of Deeds Building: The Death of Colonel Shaw at Fort Wagner

- Dwight, Illinois - Post Office: The Stage at Dawn

- Birmingham, Michigan - Former Post Office: The Pioneering Society's Picnic

- Paw Paw, Michigan - Post Office: Bounty

- Plymouth, Michigan - Purcell Station Post Office: Plymouth Trail

References

- Carlos Lopez (Wikipedia).

- Carlos Lopez (Ann Arbor District Library). Set of clippings relating to Lopez from the Ann Arbor News.

- Carlos Lopez, U-M Art Professor and Noted Painter, Dies at 44, Ann Arbor News January 7 (1953).

- George Vargas, Carlos Lopez: A Forgotten Michigan Painter, Latino Studies Series Occasional Paper No. 56 (1999).

- Felix Carlos Cuervo Lopez: The Painter Behind the Controversy. Presentation by Donna Casaceli.

- Latin American and Latino Art in the Midwestern United States (Curate ND). Material on Lopez on p. 37

- Latinx Artists at Michigan (1945-1980s): Art as a Form of Activism (¡PRESENTE! - Latinx Histories @ UM).

- Who Was Carlos Lopez (Brauer Museum of Art). Observations by the artist's son, Jon Lopez