Biography

Arthur Kimmig Getz is an artist whose work has been viewed by millions of people - not in a gallery or museum, where his paintings were signed with his middle name, but on the cover of The New Yorker magazine, where he used his last name on more than 200 paintings.

Getz was born in Passaic, NJ in 1913, the son of a factory worker. He was able to attend the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn only after his high school art teacher paid a personal visit to his parents to plead his case. While at Pratt he spent his summers as a sailor on freighters bound for West Africa.

He graduated with honors from Pratt's School of Fine and Applied Art in 1934. The same year he sold a magazine cover illustration to American Childhood and used the money to move to New York City. There he supported himself with odd jobs such as making papier mâché mannequins for the Garment District and doing industrial design for The Oscar Bach Studios.

He sold a cover illustration to The New Yorker in 1936 (not published until 1938). He married Margarita Gibbons, who had had danced with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet and become an abstract painter. Arthur and Margarita were friends with many people in the New York world of art and dance, including the Soyer brothers and Daniel Nagrin and Helen Tamiris of the Tamiris-Nagrin Dance Company.

In 1939, Philip Guston taught Getz how to mix casein tempera and suggested that Getz apply for a mural contract with the WPA. This led to four Getz murals: the Textile Building of the New York World's Fair (1939), the Lancaster, NY Post Office (1940), the Bronson, MI Post Office (1941), and the Luverne, AL Post Office (1942).

During the war Getz worked as a surveyor with a rank of First Lieutenant of Field Artillery in the Philippines. Returning to New York, he resumed his work as an artist. His magazine covers for The New Yorker span the period 1938-1988. He provided the cover art for the Edna Ferber novel "Great Son" in 1947. And he taught at the School of Visual Arts.

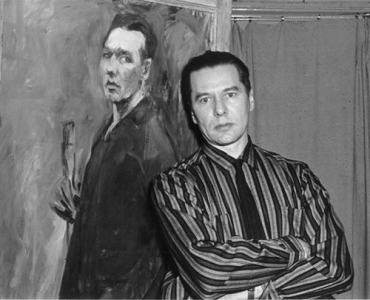

Getz did easel painting as well as illustration. He had a one-man show at the Babcock Gallery in New York in 1960. Arthur and Margarita divorced in 1963, and he remarried in 1969, to Anne Carriere. The couple moved to Sharon, CT, and Getz began painting rural scenes in addition to his standard urban fare. He wrote and illustrated a number of children's books in the 1970s and 1980s. And he taught at the University of Connecticut and the Washington Art Association in Washington, CT.

Getz and Carriere divorced in 1973. His last cover for The New Yorker was completed in 1988. In 1994 he suffered a stroke, blinding him in one eye. But he continued to paint and draw, dying in Sharon, CT in 1996.

Critical Analysis

When Getz exhibited at the Babcock Gallery in 1960, the gallery director requested that he not sign his work with "Getz," since that name was so well known for his New Yorker illustrations. Ironically, it was probably Getz's fame as an illustrator that commanded the prices he received for many of his pieces of fine art, whether he signed them "Getz" or "Kimmig."

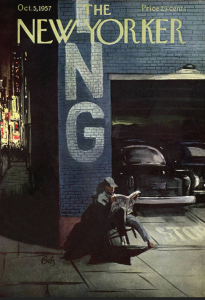

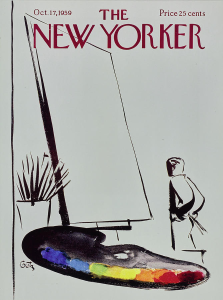

For one thing, the style of Getz's easel paintings was the same as the style of his New Yorker covers. Many of those covers have enough nuance that they would work well as paintings on their own. His editor at The New Yorker described his oevre as "...a chronicle of New York’s moods, to be set alongside Guardi’s paintings of Venice..." And it is true that Getz's cover illustrations, taken as a set, offer a vivid chronicle of the city of New York for the period 1940-1980.

Many of the cover illustrations have a depth unusual in such a medium. One, for example, simply depicts a resting garage attendant, but lights the scene brilliantly, with a few rays of light penetrating the gloom of the overall environment. Other covers are more free and easy, such as the (possibly self-reflective) image of an artist staring at a blank canvas. Almost all of his cover art invites a second look and rewards the viewer who pauses to study it in detail.

Getz did a few political cartoons in addition to his other work. These appear a bit labored in comparison with his New Yorker covers. The fact that the themes of his cover art hewed closely to Getz's everyday experiences - mostly urban scenes when he lived in New York, and rural and suburban themes once he moved to Connecticut - suggest that he liked to paint things that had just struck his attention. Perhaps, while for cover art his imagination could run free, political cartoons demanded a more restricted gaze.

Getz's Post Office murals came earlier in his career than most of his New Yorker covers. These murals involved agricultural and historical themes. In chronological sequence, his Lancaster, NY murals, "Early Commerce in the Erie Canal Region," shows goods being brought to a train station on a horse cart; his Bronson, MI mural, "Harvest," shows a prosperous farm scene; and his Luverne, AL mural "Cotton Field," depicts a farm laborer picking cotton while a foreman weighs it. Stylistically, the murals show a gradual simplification of form: the first mural has six figures, the second one three, and the third only two people. It's almost as if Getz decided to gradually move in closer and closer to the subjects he was depicting. And the compositions become more intimate and more effective in the process.

Sadly, the intimacy of the Luverne, AL mural seems to be too much for the management of the U.S. Postal Service. In recent years they have covered up (and probably irreparably damaged) this mural. This is likely a reflection of the South's inability to deal with its history of slavery. The Luverne mural is hardly an ode to white supremacy, nor a call for black power. But somehow it's made the Postal Service uncomfortable, and their response to discomfort is to hide or destroy the artwork that causes this discomfort.

Murals

- Luverne, Alabama - Post Office: Cotton Field

- Bronson, Michigan - Post Office: Harvest

- Lancaster, New York - Post Office: Early Commerce in the Erie Canal Region

References

- 1964 Industrial Construction Building (Christmas Discount Shop).

- The Art of Arthur Getz (The Art of Arthur Getz).

- The Art of Arthur Getz (Berkshire Style).

- Arthur Getz (Arthur Kimmig Getz).

- Arthur Getz (Wikipedia).

- Lee Lorenz, Arthur Getz, The New Yorker February 5 (1996).

- Arthur Getz Wall Art (Condé Nast Store).

- Cotton Field (Living New Deal). Getz mural and its desecration with plastic covering.

- Pat Achilles, Looking at Illustration: Arthur Getz – January 1958, Achilles Portfolio January 22 (2024).

- William Zimmer, Moments of an Artist's Life Captured in a Retrospective, New York Times August 24 (1997).

- Lee Lorenz, Urban Explorer/Restaurant Art of Arthur Getz, Pillar to Post August 31 (2017).