Biography

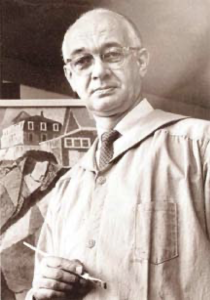

Alan Tompkins didn't paint every day of his 100-year life, but he came close, working almost daily from age 7 until a few days before his death. Although he insisted that he was a painter, first and foremost, his long lifespan included many other activities.

Tompkins was born in New Rochelle, NY in 1907. His father was an engineer and amateur painter. In 1912 the father became Deputy Commissioner of Docks in New York City. The family moved around a bit, finally settling in Bridgeport in 1917.

Alan attended military training camps in the summers of 1921-1925, enrolling at Columbia University in 1925 as a pre-engineering student. But art was his true love, and mathematics was a weak point, so he majored in history and art history, graduating with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1929.

After graduation he worked in Europe for the summer and explored art museums on the continent. Returning to the United States, he enrolled in the Yale art school, where he studied mural painting with Eugene Savage. He formed other important connections at Yale, including the portraitist and long-time faculty member Deane Keller, and Tompkins's contemporaries Donald Mattison and Henrik Mayer.

In 1933 Tompkins received a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Yale, along with the Winchester Prize, allowing him to spend eight months studying in Europe. After visits to Rome, Venice, Ravenna and Munich, Tompkins established an atelier in Paris, where he met his future wife, Florence Coy.

In 1934, Mattison, now Dean of the Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis, hired both Tompkins and Mayer. Mayer stayed in Indianapolis until 1946, while Tompkins returned to Connecticut in 1938. This was a productive period for Tompkins. He married Florence Coy in 1935 and exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1936 and the Herron Art Institute in 1938. He completed a mural for the Martinsville, IN Post Office in 1937 and another for the North Manchester, IN Post Office in 1938.

Living in Stamford, CT, Tompkins hoped to paint full-time, but he needed additional income and taught at the Cooper Union. He participated in the Annual show of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1939 and painted a mural for the Boone, NC Post Office in 1940. He painted another mural for General Electric in Bridgeport, CT in 1940 and a Post Office mural for Indianapolis in 1942. His work was shown at the Sweat Memorial in Portland, ME in 1943.

Tompkins worked as Director of Design at General Electric's Bridgeport plant from 1943-1947. During the war he was involved with development of the Bazooka rocket-propelled anti-tank weapon. Postwar, he worked on the design of household appliances such as toasters and disposals, receiving a patent for a kitchen cabinet with integrated small appliances.

After the war (1946) Tompkins returned to teaching at Columbia while his friend Henrik Mayer became Director of the Hartford Art School, then part of the Hartford Atheneum. Mayer hired Tompkins as a drawing instructor in 1951 and later as his Assistant Director. In 1957 Tompkins became Director of the Art School, when it merged with Hiller College and the Hartt College of Music to form the University of Hartford. He also completed murals for the Central Baptist Church and the Maple Hill restaurant. Mayer continued teaching at the University for many years. As Director of the Art School, Tompkins was an influential figure on the Hartford arts scene for some time. In 1969 he resigned his Deanship to become a University Professor. He retired from the University in 1974 but continued to teach art at the West Hartford Art League.

Throughout his teaching career Tompkins continued to paint and to exhibit his work. He was part of the Connecticut Academy of Fine Arts Annual exhibit from 1952-1971, winning first prize for painting in 1968-1970.

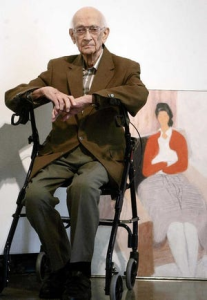

In 1984 Tompkins had a solo exhibition at the Gallery on the Green in Canton, CT. The University of Hartford honored him with a Doctor of Fine Arts degree in 1990. He moved into a retirement facility in 1990 but continued to paint on a regular basis. He had a solo show at the Hartford Art School not long before his death in 2007. A retrospective of Tompkins's work was mounted at the Celeste LeWitt Gallery at the UCONN Health Center in Farmington, CT in 2011.

Critical Analysis

In his Post Office murals, Alan Tompkins solved a problem whose solution had eluded many of his contemporaries. The space above a Postmaster's door, where the murals were typically placed, tended to be long and narrow. Artists sometimes struggled to fill this space in a manner that could engage the viewer across the full width of the canvas. Tompkins dealt with this issue by creating sets of images that involved motion across the entire width of his composition. In his Martinsville mural, for example, he shows a set of people reading their recent mail - some elated and some dejected. the mail recipients are all walking from left to right, and the viewer naturally follows their progress across the canvas.

Tompkins's Indianapolis mural is a simple street scene, but again there is motion from right to left, and the viewer's gaze is led from the cyclist and mailman on the right across to the grocer on the left. In this manner Tompkins avoids the static feeling that occurs when the muralist places a series of figures across the canvas with no dynamic connection among the people depicted.

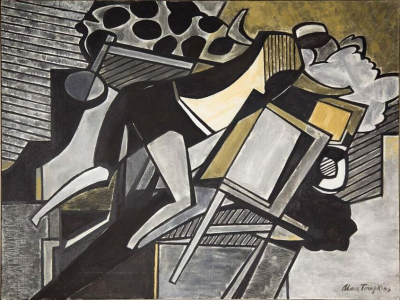

While Tompkins's murals were, naturally enough, styled according to the American Scene, his other paintings were much more abstract. But in those paintings, too, he fills the canvas in an engaging manner and helps to keep the viewer's eyes moving across the work.

Tompkins's role as dean of the Hartford art scene was not without controversy. When the new Civic Center was being built in Hartford, Tompkins was free with his advice and criticism. In particular, while he initially supported a Sol LeWitt submission for the project, he later criticized LeWitt's abilities as a muralist and described his proposed work as "weak and incapable of arousing aesthetic response." He lamented that greater consideration was not being given to local artists, although LeWitt himself was a native of nearby New Britain. Tompkins urged Hartford to cast off its traditional risk-aversion as the "Insurance City." But perhaps it was Tompkins himself who hesitated to risk the public display of LeWitt's overtly geometric composition, which eventually found a home in the Hartford Atheneum.

Murals

- Indianapolis, Indiana - Broad Ripple Station: Suburban Street

- Martinsville, Indiana - Post Office: Arrival of the Mail

- North Manchester, Indiana - Post Office: Indiana Farm - Sunday Afternoon

- Boone, North Carolina - Post Office: Daniel Boone on a Hunting Trip to Watauga County

References

- Alan Tompkins (askART).

- Alan Tompkins (Papillon Gallery).

- Alan Tompkins (New Britain Museum of American Art).

- Alan Tompkins, Hartford Courant December 8 (2007).

- Alan Tompkins ’29: A Passion for Painting (UConn Health). By Daniella Zalcman.

- Dave Collins, Alan Tompkins still at the canvas as his 100th birthday approaches, Telegram & Gazette August 12 (2007).